Canada appears to be struggling on both NAFTA fronts: the U.S. and Mexico.

While spats with the U.S. grab all the headlines, Mexico has gone largely unnoticed. Yet, there are big issues at play. When Mexico does come up, the problem seems to be more fundamental – not just how to engage, but whether Canada should even engage at all.

The problem is two-fold. First, Canada rarely includes Mexico in its discussions about renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This one is critical, as Mexico may actually hold some of the most important cards when it comes to leverage with the Americans in the negotiations.

The second problem is the “Throw Mexico under the bus” concept that pops up from time to time.

In the modern era, trade and political talks in North America have always been a dynamic mixture of bi- and trilateral negotiations. The idea that all three nations will always sit down together to discuss every detail of every issue does not work. There are specific issues on particular topics in the North American context that are of little, if any, interest to one party, or issues where two of the parties have a problem that does not relate to the third.

That Canada would seek to advance negotiations on some issues directly with the U.S. just makes sense. But those issues that are best handled one-on-one with the U.S. doesn’t mean Canada is negotiating the entire treaty without Mexico (which would actually be impossible because it is a trilateral treaty). So, the idea that Canada would seek to renegotiate only the with the U.S., or throw Mexico under the bus, is a non-starter.

The President Trump factor

But if everyone knows that (or should know that) then why the current ruffled feathers in Mexico? Why does Mexico and the Canadian media seem to believe that Canada is throwing it under the bus, let alone that such a thing is possible?

The answer may be in the early reaction in Mexico to Donald Trump. When Trump was using Mexico as his favourite piñata, the silence out of Canada was deafening. It may be that Mexico took the fact that Canada didn’t jumping to its defence as being thrown under the bus.

But it’s one thing to throw someone under a bus and another to decide TO not jump down there with them.

The approach of the Canadian government appears to be to try and keep to the high road, to not get suckered into responding to every outrageous tweet and histrionics out of the White House. A measured approach, even as the president moves from threatening Canadian softwood and to ending NAFTA.

To be fair to Mexico that’s easier for Canada, which never received the same level or types of threats and insults hurled by Trump in his attempt to win the White House.

It appears now that Mexico has landed on the same approach on how to deal with Trump.

Mexico’s trade advantage

That takes us to the second point – the importance of Mexico for NAFTA renegotiations .

Canada doesn’t seem to have noticed, but Mexico may actually be holding more leverage in upcoming NAFTA negotiations.

Take the difference between corn and coal. In response to U.S. tariffs on Canadian softwood tariffs, B.C. premier Christy Clark threatened retaliation against U.S. thermal coal shipments going through the province’s ports – an action that severely damage the politically important states of Wyoming and Montana with their combined six electoral college votes. Mexico on the other hand saw its Senate pass a resolution calling on the government to lower tariffs and facilitate imports of corn and other agricultural products from Argentina and Brazil.

In other words, do what ever is necessary to ensure that market forces drive a switch from American imports. Corn is a critical crop in four U.S. states and seven other states produce more than 500,000 bushels a year. Corn is the largest recipient of farm subsidies and Mexico is the largest buyer of U.S. corn. And that’s just corn; Mexico is looking to target other crops as well.

So, it was no wonder that new U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue was the most vociferous critic of Trump’s musing to immediately curtail NAFTA. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross went to the White House with arguments to talk Trump out of ending NAFTA, Secretary Perdue showed up with charts, diagrams, and electoral maps. Energy Secretary Rick Perry who apparently doesn’t appear to be getting any face time with the new president, stayed home.

On the security front, Mexico also has the ‘nuclear’ option of slowing or curtailing security co-operation with the U.S. Should Mexico start waving through migrants from Central America – which is the largest source, not Mexico – to the U.S.-Mexico border, then the administration has a potential crisis on its hands.

Of course, Mexico will be damaged, perhaps more so, by these actions. But with the Senate resolution to move agricultural imports from the U.S. already passed, it’s showing that it has power and the guts to use what power it has.

An election that could change the equation

But the most powerful weapon Mexico has may be the upcoming July 2018 federal elections. As Mexico does not allow re-election for federal office, a completely new congress and president will be elected, with congress sworn in in September and the President on December 1st.

The current frontrunner for president is Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, a left-wing populist who is as, if not more, opposed to NAFTA than Bernie Sanders.

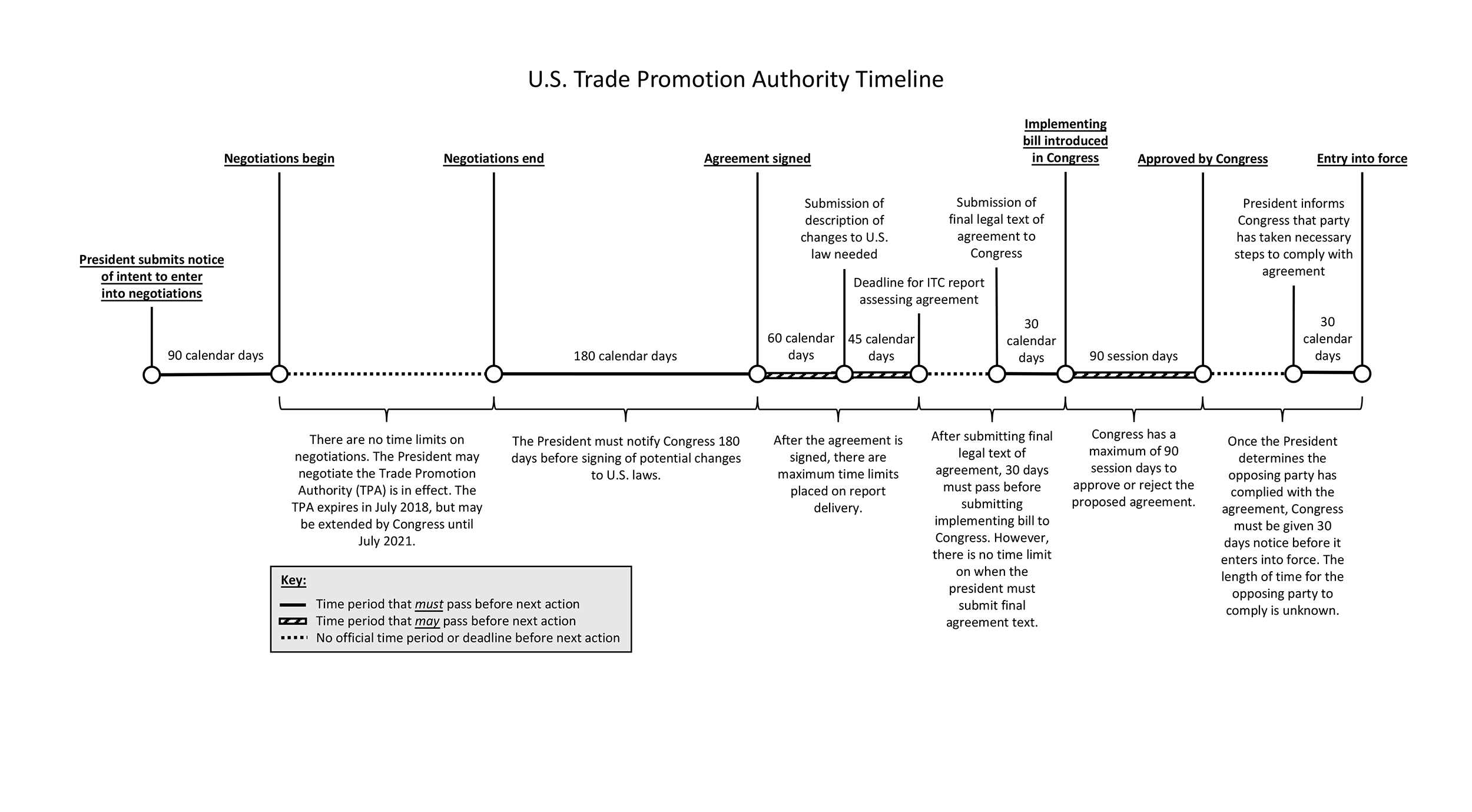

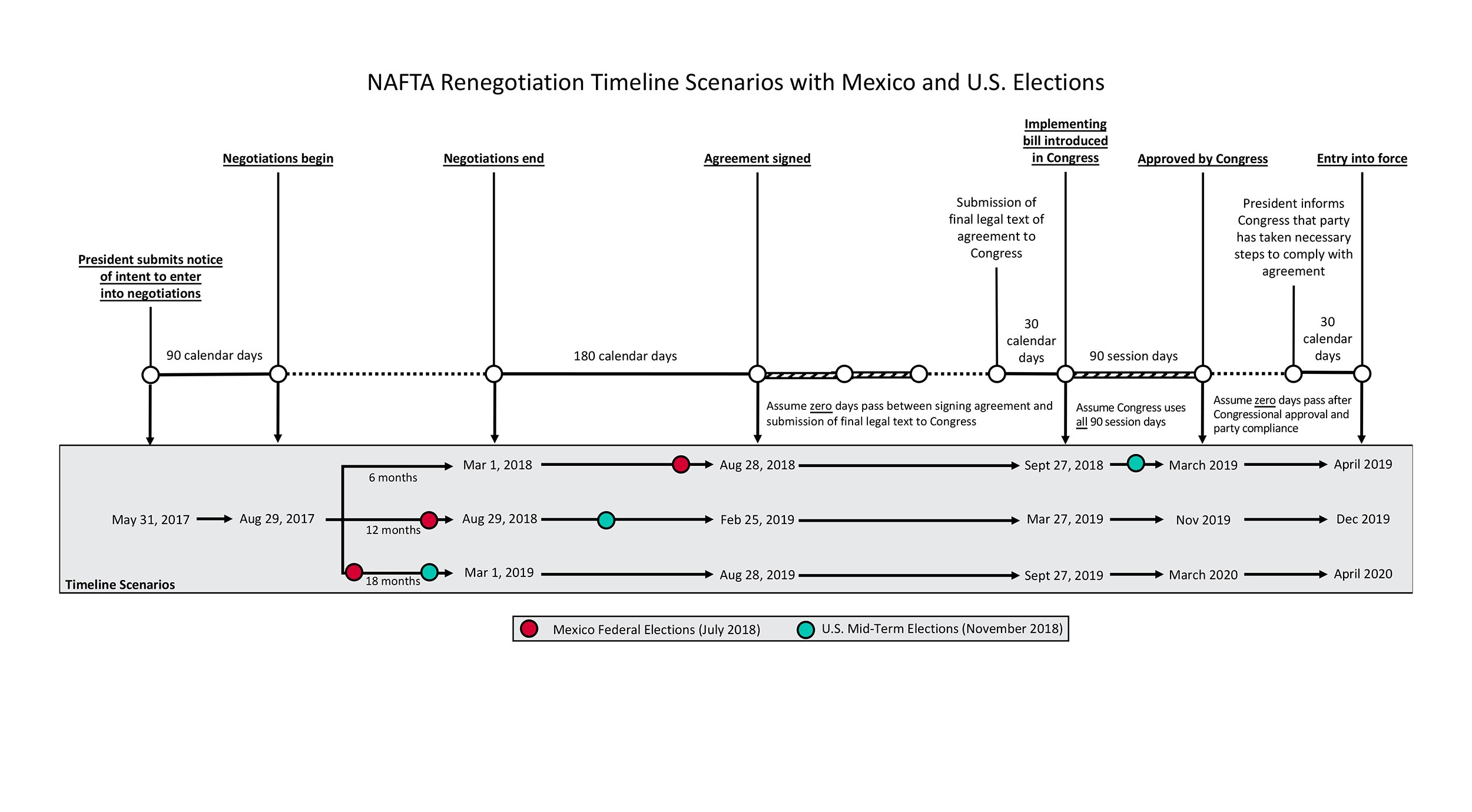

Given the statutory timelines for negotiating, tabling, reviewing and voting on trade agreements in the U.S. under trade promotion authority (TPA), it is inconceivable that a new NAFTA could be negotiated and ratified before the Mexican elections and unlikely that it could be done before the U.S. mid-term congressional elections in November 2018. Taking a most optimistic scenario with negotiations taking only six months the earliest an agreement could be presented to congress would be in September 2018, right before the U.S. mid-term elections.

It is difficult seeing any scenario where the U.S. congress would vote on a new NAFTA agreement right before the mid-term elections. If the U.S. congress decides to take up an agreement in a lame duck session that would likely mean a final vote right before a new Mexican president is sworn in on December 1st.

Depending on the outcome of the Mexican presidential race it could be back to square one if the incoming president has serious objections. A not unlikely scenario if the new president is the left of centre candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

U.S. Trade Promotion Authority Timeline

(Select image for high resolution)

NAFTA Renegotiation Timeline Scenarios with Mexico and U.S. Elections

In all of this, Canada is going to be a passive observer, watching as the negotiations get bounced from bad to worse, from Guata-mala to Guata-pior (from bad to worse) as the talks get sucked into the campaign cycle and what is sure to be even uglier anti-NAFTA rhetoric in the U.S. and potentially in Mexico.

The Mexican electoral cycle appears to be the more influential, as it will produce an entirely new congress and a new president. Mexico also has the leverage in the short-term with its ability to use this coming change in Mexico to press the U.S.

So, for Canada it may be time to apologize for not jumping to Mexico’s defence, urge that bygones be bygones – and start thinking of how to ride the electoral cycle together.

– Carlo Dade is Director of the Trade & Investment Centre