On March 29, 2016, the Wilson Center’s Canada Institute in Washington, D.C. convened a panel for a timely discussion of key political and market factors affecting bilateral lumber trade, and its broader impact on the Canada-US trade relationship. In this pivotal year, there is an appetite for a historical look at some of the key figures, considerations, and milestones leading up to, and during the implementation of, the 2006 Softwood Lumber Act and informed analysis of what might lie ahead.

Broadcast live streaming video on Ustream

Canada West Foundation policy analyst Naomi Christensen gave the following presentation

The expiration of the Softwood Lumber agreement, and what happens next, will have an impact on the western Canadian economy. The majority of Canada’s softwood lumber production and exports come from the West.

Over the near decade the SLA was in place, many of the major factors that affect the softwood trading relationship between Canada and the U.S. have changed.

The six main factors that changed are

• U.S. housing starts

• Canadian timber supply

• Integration in the North American lumber market

• The price of lumber

• Currency exchange rate, and

• Canada’s customer base for softwood lumber.

The analysis of how these factors changed indicates there is little incentive at this time to sign a new SLA.

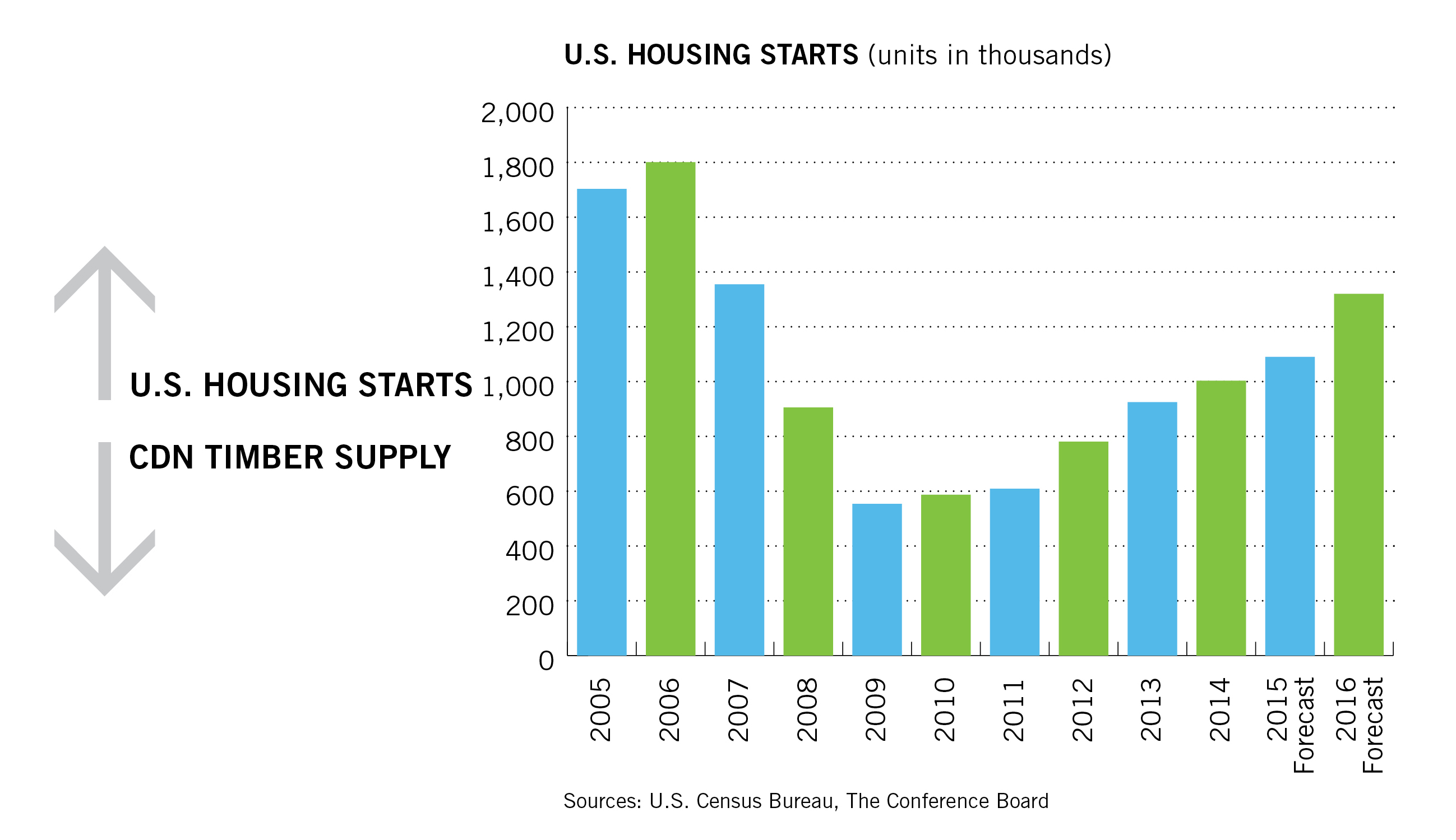

Housing Starts

The combination of rising U.S. housing starts and declining Canadian timber supply is one of the reasons the SLA expired with little fanfare.

In short, the U.S. economy needs Canadian softwood, and Canada is less of an economic threat to U.S. market share because the Canadian timber supply is declining.

As you can see in this graph, it was just shortly after the SLA was signed in 2006 that U.S. housing starts began to decline.

For most of the time the SLA was in place, housing starts were declining or stagnant. The upswing started around 2012, and last year for the first time since the Great Recession, starts once again broke the one million mark.

Softwood lumber demand in the U.S. exceeds domestic supply, and 96% of the softwood lumber the U.S. imports comes from Canada.

If that Canadian supply weren’t there, what would happen?

If lumber imports from Canada were more restricted under new terms in a new agreement, housing construction, and its associated jobs, could feel the impact.

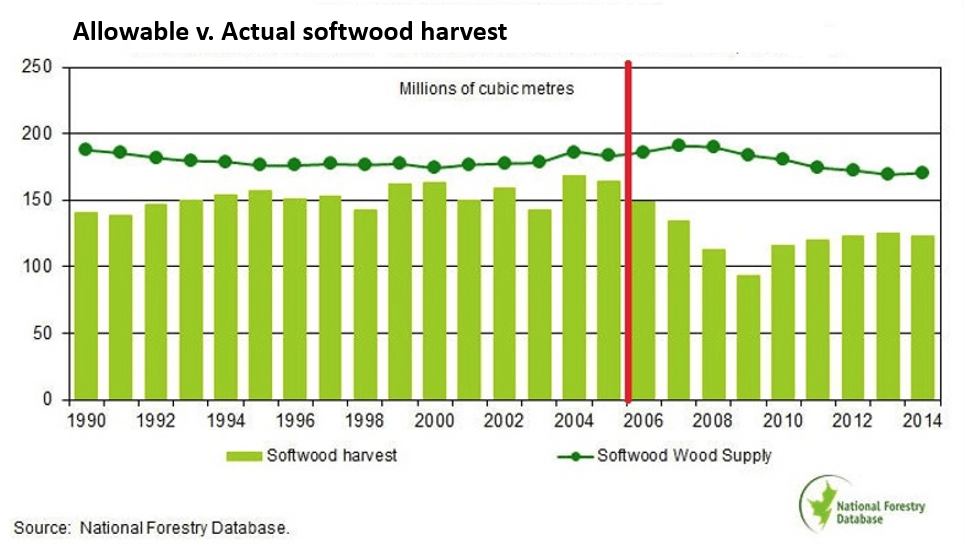

Canadian Timber Supply

To the right of the red line on this graph you can see both Canada’s supply and harvesting of softwood since the SLA was implemented. On both counts, we are below traditional levels.

In Quebec, the second largest softwood producing province, government conservation policy has decreased the volume of timber available for harvest. In western Canada, the mountain pine beetle is the cause.

Mountain pine beetle was originally confined to one province, but that one province happened to be British Columbia, where more than half of Canada’s softwood lumber production takes place.

In 2006, the beetle spread to Alberta. Because it is now infecting jack pine as well as lodgepole pine, it’s possible it will keep moving east across the rest of Canada.

Although the infestation in peaked in B.C. in 2005, the effects on timber supply are going to last decades.

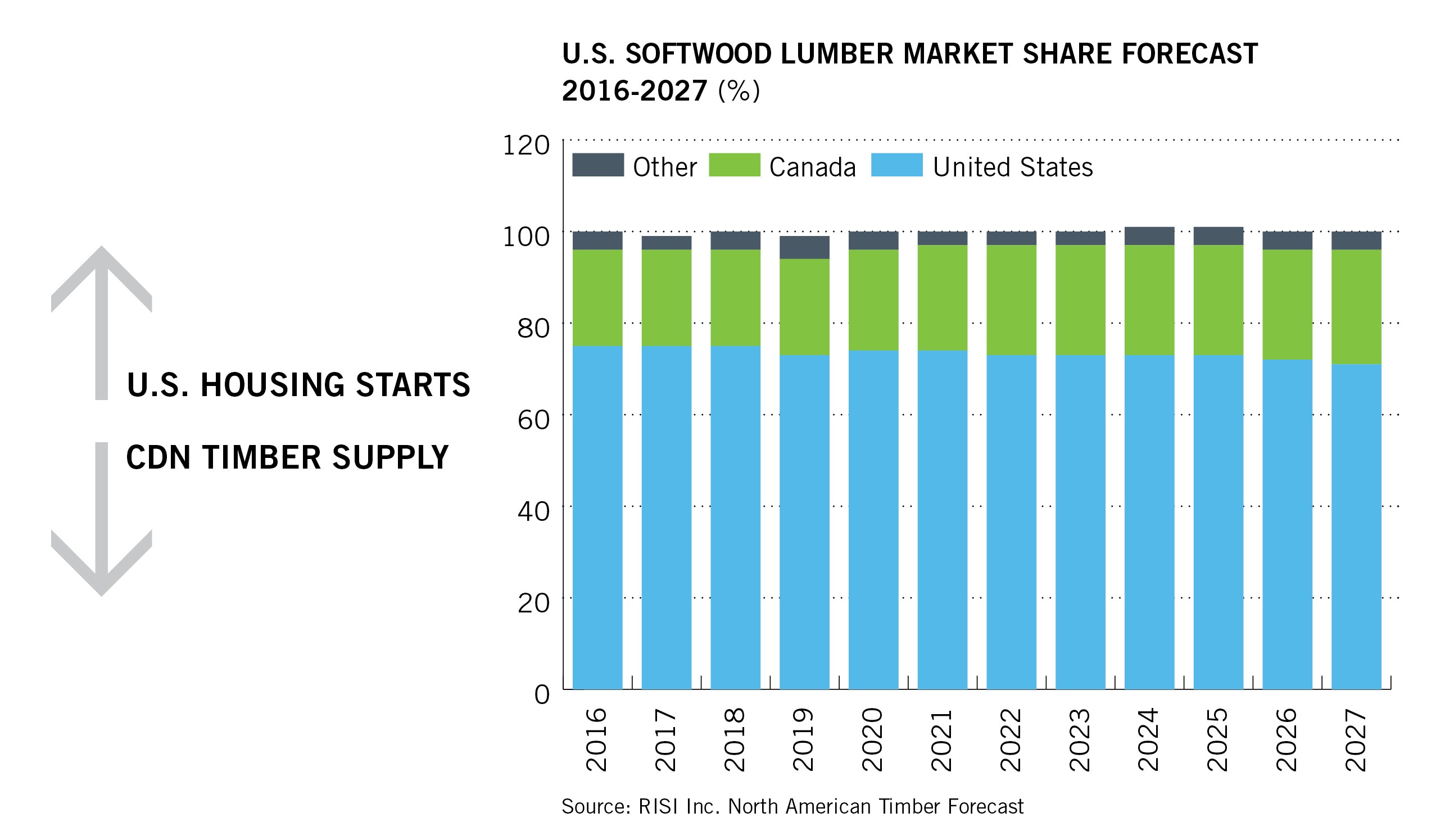

The graph on this slide really tells the story. Canada’s decreasing timber supply means its share of the U.S. softwood market will also decrease.

The SLA capped Canadian softwood at occupying a maximum of 34% of the market. Historically, Canada has held about 30%. Canada didn’t come close to the cap during the 9 years the agreement was in force.

Right now, Canadian softwood occupies about 27% of the U.S. softwood lumber market.

Once timber salvaging is no longer feasible, Canadian harvest levels will decline even further.

Look at the last bar on this graph.

Because of declining supply, Canada is forecast to hold about 25% of the U.S. softwood lumber market 10 years from now. That is almost 10% less than the SLA cap.

Even if Canada wanted to dramatically increase its exports to the U.S., it does not have the physical capacity to do so. Nor will it have the capacity to do so in the next few decades.

It is also interesting to note that during the 9 years the SLA was in place, the U.S. share of its own lumber market increased ten per cent. On this front, the SLA succeeded in its aim to protect U.S. market share for domestic producers.

Integration

Canada’s timber situation is in stark contrast to the U.S. South where there is excess supply. While mills in Canada have been closing, Canadian companies have been buying mills in the southern and western United States to make up for declining supply in Canada.

In the year 2000, two U.S. mills were bought by a Canadian company. Today, three of the largest lumber companies in western Canada combined operate more sawmills in the U.S. than they do in Canada.

In the big picture, Canadian companies are still a minor player in the U.S. Combined, they own less than 5 per cent of the total numbers of mills. But, there is certainly a lot more integration now than there was a decade ago.

In looking at public statements about Canadian acquisitions of U.S. mills, the stability of owning operations in the U.S., which would be unaffected by future trade disputes, was certainly one of the drivers of these investment decisions.

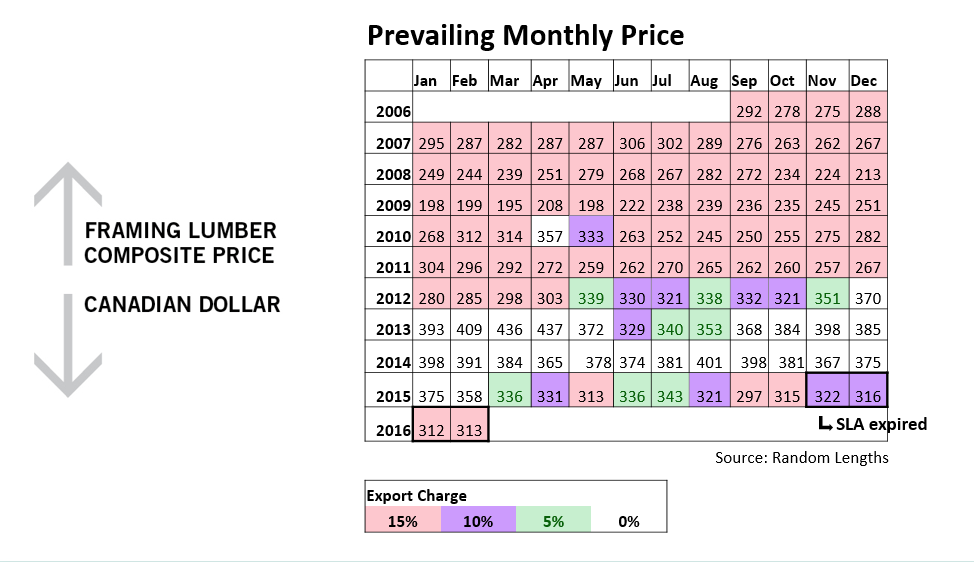

Price of Lumber

Under the 2006 SLA, the export charge placed on Canadian lumber varied depending on price.

In this chart, red indicates the months when the export charge was 15% – the highest it could be. Purple shows when the charge was 10%, green is 5% and white means there was no charge.

For the majority of the time the SLA was in place, the 15% export charge applied.

In the last few years of the agreement, prices rose enough that Canadian exporters were able to forgo paying the highest export charge.

With high prices, Canadian exporters had the double benefit of receiving higher prices for their product, and paying lower – or no – export charges.

Even though export charges applied for most of 2015 – and would have been applied in the months after the agreement expired had it still been in place – expect the fact that there was no export charge placed on Canadian softwood for much of 2013 and all of 2014 to influence the current negotiations.

Currency

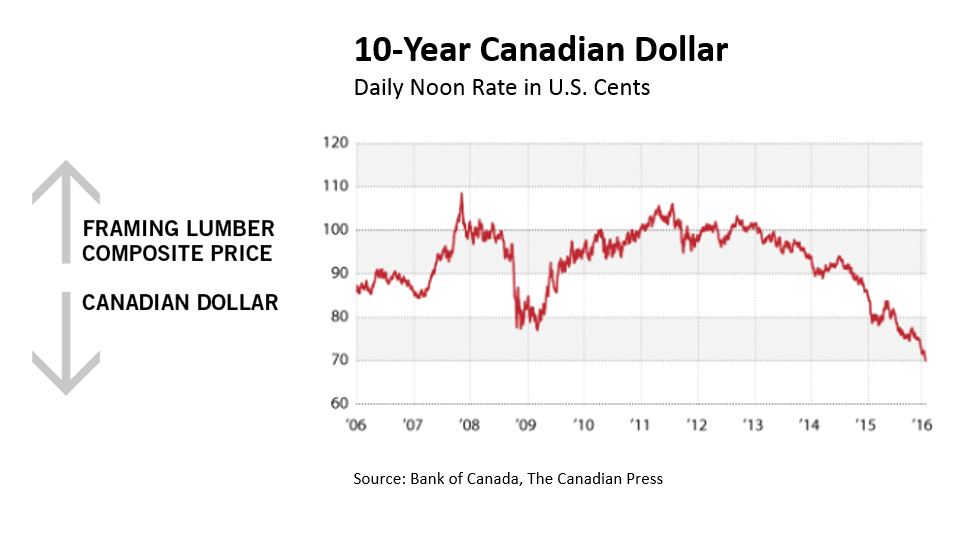

The value of the Canadian dollar also changed over the last 9 years.

The Canadian dollar was not on par with the U.S. when the SLA was signed in 2006. It was hovering around 90 cents, which is still higher than it is today.

At 76 cents today, the Canadian dollar is even lower than it was in 2009, during the Recession.

In the short term, Canadian softwood lumber exporters are reaping the benefits of higher profits from a lower dollar.

However, in the long-term, expect it to be a catalyst for more restrictive measures in any new agreement.

The challenge here will be negotiating a long term deal that accounts for currency fluctuations.

Customer base for Canadian softwood lumber

For the most part, the SLA was viewed favourably in Canada because it brought stability and predictability for exporters when dealing with their largest customer.

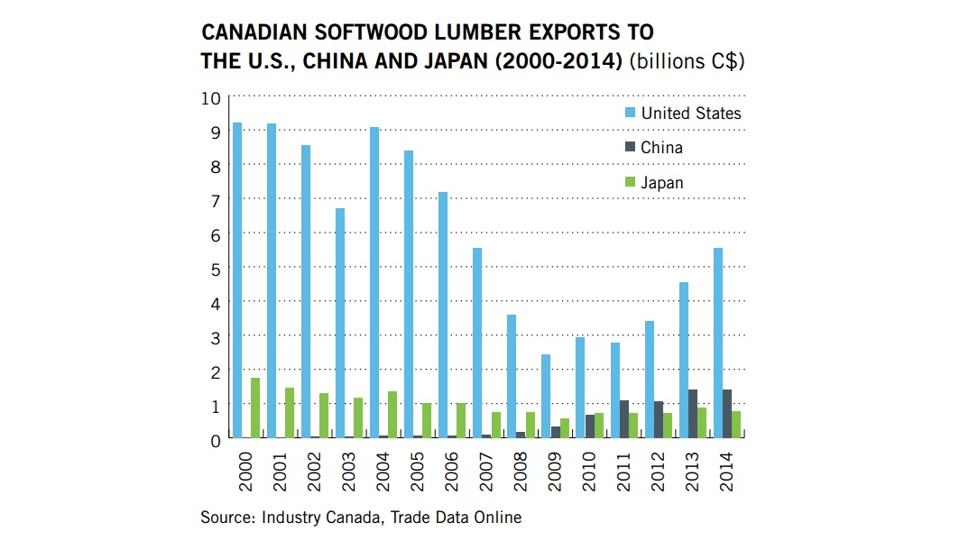

In 2006, the U.S. was by far the biggest customer of Canadian softwood lumber – as it had always been. 82% of the total amount of Canadian softwood lumber exports went to the U.S. that year.

As this graph shows, after the deal was implemented, Canadian exports to the U.S. began to decline.

By 2011, only 53% of Canada’s softwood lumber exports went to the U.S.

This occurred because of the coinciding events of the housing crisis in the U.S., economic growth in China, and the need to salvage mountain pine beetle eaten timber. This situation allowed Canada to increase softwood lumber exports to China significantly.

In 2006, China accounted for less than 1% of Canadian softwood exports. Five years later, in 2011, 21% of exports went to China, and British Columbia had become the leading global supplier of softwood lumber products in China.

Since 2011, exports to China have been fairly stagnant as that economy slows, and exports to the U.S. have been increasing as the housing market recovers. Yet even this scenario maintains the big shift made in Canada’s softwood customer base. Exports to the U.S. are still far below historical averages.

The ongoing trade dispute with the U.S. over softwood lumber has motivated both industry and government in Canada to seriously pursue new customers for softwood lumber. This process takes time, but it is happening.

Although the U.S. is still Canada’s largest customer, Canada is less reliant on the U.S. market today than during any other point in our softwood trading relationship.

Last Observation

The original date for the expiry of the SLA was 2013. A clause was written in that allowed the agreement to be renewed for two additional years.

Canada and the U.S. started talking about using the clause in 2011, two years before the expiration deadline.

When it came to the recent 2015 expiration, there was very little two-way communication on the subject.

From a Canadian perspective, it seemed pretty apparent at the U.S. was very focused on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and softwood was on the backburner.

It was not a surprise when the agreement expired without a new one in place.

It is not a surprise that the two countries are back at the negotiating table.

What I think will be a surprise is if a new agreement is reached before the standstill clause on trade litigation lifts in October.

Naomi Christensen is a policy analyst, and author of Branching Out: Preparing for life without a Softwood Lumber Agreement.