Strong Signals: China’s changing trade direction and what it means for Canada

Sharon Zhengyang Sun, Trade Policy Economist, Canada West Foundation

January 2019

Skip to pdf

Sharon specializes in international trade and investment policy-related research. Her current focus is Chinese industrial policy and its impacts on Canadian sectors.

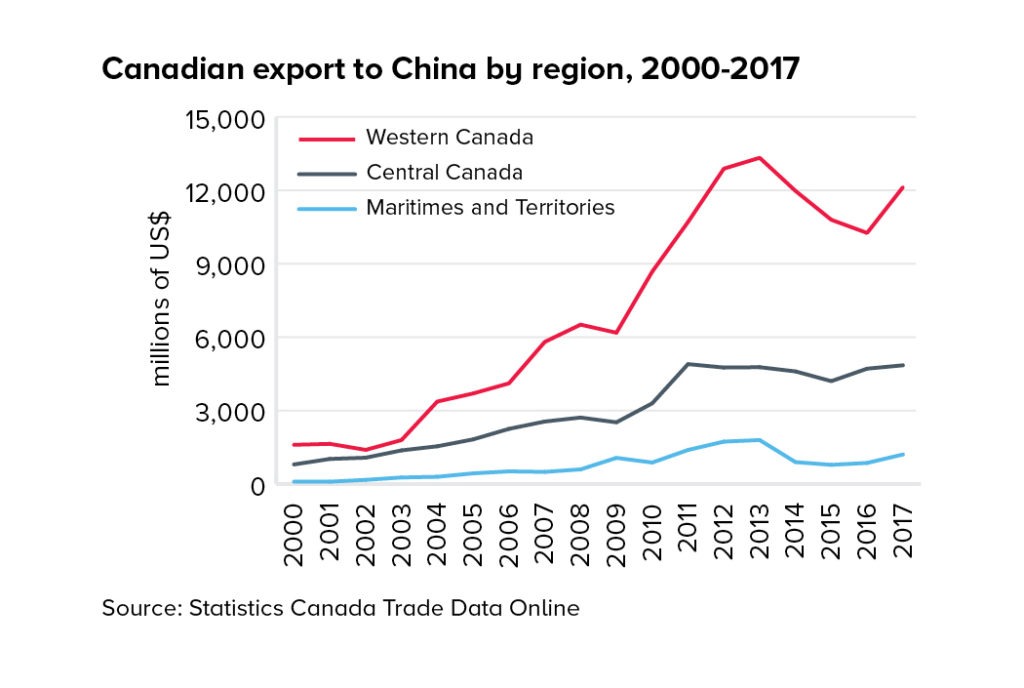

There are strong signals that China – Canada’s second-largest trading partner – is changing its trade direction and becoming more self-sufficient in advanced manufacturing. If Canada does not pay attention, it will miss opportunities to expand trade in China and defend its interests at home. The current trade war between Canada’s two largest trading partners, the U.S. and China, and the uncertainty in the Sino-Canadian long-term economic relationship emphasize the urgency for Canadian businesses, trade negotiators and policy-makers to understand China’s new trade direction.

Made in China 2025 (MIC2025) is China’s economy-wide industrial policy to become a superpower in advanced manufacturing capacity and technologies. Understanding MIC2025 and its trade policy implications can help improve trade co-operation with China, mitigate risks and find new opportunities to diversify Canadian imports and exports. The plan has been widely studied in the U.S., Germany and the European Union, but it has not yet received the same scrutiny in Canada. It should.

This policy brief provides an introduction to MIC2025 and identifies a number of Canadian sectors that may be affected. It also raises research questions that the Canada West Foundation will examine in the future.

What is MIC2025

Launched in 2015, MIC2025 is China’s stated industrial policy to overcome the “middle-income trap,” a critical economic issue in which a developing nation’s growth stagnates after reaching middle-income level and fails to transition to high-income levels. China’s ambition is to become a competitive economy characterized by services, sustainable domestic consumption, higher value-added manufacturing and increased domestic innovation capacity.1

An industrial policy such as this is not unusual; Germany, South Korea, Japan and the U.S. have or have had similar policies. The difference with China, however, is the level of state involvement, the level of integration across industries and alignment across all levels of government to carry out MIC2025. It also has an aggressive deadline. These differences are in no small part due to the ability of the Chinese government to control its economy and regulatory environment in ways that democratic governments cannot.

Further reading: WHAT NOW? Policy Brief | Strong Ties: Canada & China’s economic relationship

MIC2025 is planned to be the first of three 10-year efforts to achieve greater self-sufficiency in specific advanced manufacturing sectors. These sectors include power equipment, advanced agricultural machinery and equipment, renewable energy vehicles, marine and aerospace equipment, and biomedical and high-performance medical devices. The plan emphasizes co-operation among all levels of the government, public and private enterprises, universities, research institutions and foreign companies. Its goal is to create a “collaborative innovative system” that integrates the “industry chain,” “innovation chain” and the “resources chain.”2 For example, China’s US$3.8 trillion digital economy in 2018, which rose by 18 per cent from the previous year and accounts for one-third of the country’s GDP, will integrate and modernize sectors such as agriculture.3

MIC2025 is a strong signal of China’s trade and investment directions because it aligns with China’s Five-Year Plans of domestic reform and Belt-and-Road Initiative development strategy. It also integrates with China’s free-trade zones and urban supercity clusters. These market-oriented areas meet global standards in regulations, business practices and infrastructure, and permit freer international flow of goods, services and capital.

What MIC2025 means for Canada

A preliminary analysis identifies the following opportunities and risks for Canadian businesses.

Smart agriculture

Under MIC2025, China’s interest in developing advanced agricultural machinery and equipment aligns with Canada’s strength and initiatives in smart agriculture. This presents opportunities for Canadian equipment export, technology licensing and crop optimization research collaborations. Smart agriculture uses technology, such as the application of modern information and communication technologies into agriculture, to sustainably increase agricultural productivity and incomes. For example, Olds College’s Smart Farm conducts research and field tests using real-time soil and plant responses with data management solutions to increase bushels per acre.4

There may be short-term gains for smart agriculture equipment and technology export. But as Chinese production increases, China’s aim to increase its own smart-agriculture development capacity by 2025 may hurt Canadian agriculture export volumes in the long term. Canola and soybeans are among the top five Canadian exports to China. As of 2017, 96 per cent of China’s canola was imported from Canada. However, even with greater production capacity in China, demand may continue to outstrip supply. Canada needs to watch these developments closely. At the same time, Canada should expect an increase in animal feed exports as China continues to grow landless industrial livestock production systems.

Clean technology

MIC2025’s emphasis on clean energy and power equipment sectors aligns with Canada’s climate change and environmental goals. This suggests potential export, licensing and joint research opportunities for emissions reducing technologies, services, processes and equipment such as water recycling, ultra-clean emission coal-fired power units, and carbon capture technologies. For example, Saskatchewan’s commercial ultra-clean emission coal-fired power plant, that uses carbon capture and storage technology, is the first of its kind and has captured an average of just over 46 per cent of its CO2 emissions since January 2015.6 Coal remains the largest source of energy in China at just over 60 per cent of its energy mix as of 2017.7 Another example is demand for soil remediation and land reclamation techniques and technologies, particularly for abandoned mining and other contaminated sites. Twenty per cent of China’s 133 million hectares of farmland is heavily contaminated, making it unsuited for cultivation.8

Liquefied natural gas (LNG)

China’s desire to replace coal with cleaner energy sources presents export opportunities for the Canadian oil and gas industry, particularly liquified natural gas. For example, PetroChina is one of the four Asian investors in the recently approved Shell LNG Canada project. The project, an LNG export terminal in Kitimat, B.C., is expected to export eventually as much as 26 million metric tons per year, primarily to Asia.9 In 2017, China was the world’s second-largest LNG importer after Japan,10 but Canadian LNG only accounted for less than 0.001% of China’s total LNG import of over US$14 billion.11 Increased LNG exports can help China decrease GHG emissions and overall environmental impact.

Electric vehicles, metals and minerals

China aims to have electric vehicles (EVs) account for 40 per cent of its total auto sales by 2025.12 MIC2025’s focus on the development of EVs could be an opportunity for Canadian copper, lead, zinc, nickel and cobalt exports, metals and minerals used to manufacture high capacity batteries.13 China is Canada’s seventh-largest purchaser of cobalt in 201714 , amounting to US$ 3.7 million, and this is expected to increase.

Canada can also play on the technology side. For example, Ballard Power, a B.C. producer of proton exchange membrane fuel cell products, partnered with Chinese companies, such as Guangdong Nation-Synergy Hydrogen Power Technology, to deliver zero-emission fuel cell transportation solutions in China.15 Therefore, Ballard is already part of China’s energy-efficient vehicle ecosystem with room to develop in the domestic market and bring back new R&D and market learning through co-operation.

Risks and challenges

MIC2025 is not without risks for Canada. For example, MIC2025 emphasizes strengthening internet infrastructure and deepening internet application in the manufacturing field by using it to carry out, network collaborative design, precision marketing and media brand promotion, to establish a global industrial chain system. However, the policy does not address international concerns about the Chinese government control of data, information and internet monitoring of Chinese enterprises as they enter international markets. This is particularly an issue for China’s digital industry and will continue to cause international friction as Chinese e-commerce and information technology businesses such as Huawei, ZTE, Xiaomi, Alibaba, Tencent, and Lenovo become more prominent on the world stage. In other words, China’s own data and internet control will become a barrier to the expansion of its own digital industry that MIC2025 aims to push, including its e-commerce and information technology businesses.

The recent concern over Huawei’s 5G infrastructure entering the Canadian market is an example of this issue. The U.S., Australia and New Zealand have all banned Huawei’s 5G technology. Huawei is just the beginning of a greater problem as the Chinese information technology industry becomes more prominent globally. MIC2025 was arguably one of the triggers that set off the current U.S.-China trade war as the U.S. identified similar issues with MIC2025 in its 2017 investigations.16 The controversy surrounding the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou is an example of further escalation.

What should Canada do?

As tensions escalate between the U.S. and China, Canada must walk the line between not provoking either giant, and pursuing Canadian economic interests. China’s position as Canada’s second-largest trading partner will most certainly not change in the near term. Canada and China will continue to trade, but Canada needs to analyze and respond to the signals of MIC2025 accordingly.

While MIC2025 aims for China to achieve some level of self-sufficiency in key areas identified in this brief, China will not be able to do everything on its own. There will be gaps which Canada can fill and in so doing, seize new business opportunities. Capturing major share of even a small Chinese market could be worthwhile for Canadian businesses and economy. These opportunities can allow Canada to gain competitive advantage in the Chinese markets and lay a foundation for future expansion in related areas of business as the Chinese economy grows and continues to shift. Finally, China’s drive to become more self-sufficient in specific sectors does not mean it will stop importing. A 40 per cent self-sufficiency goal in semiconductor production by 2025, for example, will not mean that China will no longer import semiconductors. Nor does it necessarily mean domination of the global semiconductor industry.

While a preliminary look at MIC2025 identifies some areas of potential co-operation and concerns between Canada and China, much more work is needed to determine the detailed opportunities and risks for businesses and policymakers. Major questions remain, including: the short-, medium- and long-term effects of MIC2025 on Canadian sectors; mechanisms in place to support businesses in the identified areas of opportunity and the policy measures to mitigate possible harm in others; where do Canada and China converge and diverge in trade interests; and, where are Canada’s priorities for trade discussions – including non-tariff barriers?

The Canada West Foundation will examine these questions in greater detail in future research.

1 Malkin, Anton. “Made in China 2025 as a Challenge in Global Trade Governance: Analysis and Recommendations.” Centre for International Governance Innovation. No. 183. 2018.

2 Translated from the original Notice of the State Council “Made in China 2025” in 2015. Original text: Accessed Nov 7, 2018. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-05/19/content_9784.htm

3 Qiu, Stella, and Ryan Woo. “China to boost $4.9-trillion digital economy, Xi calls for self-reliance.” The Globe and Mail. September 2018. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-china-toboost-49-trillion-digital-economy-xi-calls-for-self/

4 Old’s College. “Smart Farm.” 2018. https://www.oldscollege.ca/about/olds-college-smart-farm/index.html

5 Bai et al. “China’s livestock transition: Driving forces, impacts, and consequences.” ScienceAdvances. Jul 2018. http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/7/eaar8534

6 Seal, Joelle. “SaskPower’s carbon capture future hangs in the balance.” CBC news. November 2017. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/saskpower-carbon-capture-future-1.4414985

7 Feng, Emily. “China’s annual coal consumption rises for first time in 3 years.” Financial Times. February 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/5d351276-1c48-11e8-aaca-4574d7dabfb6

8 Dong et al. Financing Models for Soil Remediation in China. Chinese Academy for Environmental Planning. August 2018.

9 Pittman, Sarah. “China Brief, Edition 012”. Canada West Foundation. October 2018. https://cwf.ca/news/blog/china-brief-edition-012/

10 Tsafos, Nikos. “How Is China Securing Its LNG Needs?” Center for Strategic and International Studies. January 2019.

11 Canada West Foundation calculation using Statistics Canada Trade Data Online database and Comtrade database. 2019

12 Hernandez, Marco. “The stones in the road for China’s 2025 plan on electric vehicles.” South China Morning Post. October 2018. https://multimedia.scmp.com/news/china/article/2169344/china-2025-electric-vehicles/index.html

13 Clean Energy Canada. Mining for Clean Energy – Tracking the Energy Revolution 2017. June 2017.

14 After Japan, Norway, U.S., Belgium, Netherlands and Singapore in this order. From Statistics Canada Trade Data Online database 2019.

15 Ballard Power. “About Ballard: Ballard in China.” Last modified 2019. http://ballard.com/about-ballard/ballard-in-china

16 Crabtree, James. “Defense of supply chains must begin in Bali.” Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. October 2018. https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/gia/article/defense-of-supply-chains-must-begin-in-bali