August 2019

Taylor Blaisdell

Getting from A to B or finding a place to stay on a weekend getaway has never been so easy. Statistics Canada reports that the sharing economy has now become an annual $1.3 billion industry in Canada, which is only slightly smaller than Canada’s fishing, hunting and trapping industry. Globally, the sharing economy is estimated to grow into a $335 billion industry by 2025.

From 2015 to 2016 in Canada, the number of active Airbnb’s nearly doubled. Private rentals jumped from 52,000 to 100,500 while the number of hotels increased at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of just under 1 per cent.

The growth of the sharing economy has rapidly outpaced regulation. Provinces across the West are facing challenges regulating this tech-driven economy, and for good reason. While this new economy provides opportunity for innovation and economic prosperity, it also breeds risk for those who participate. Disruption of traditional industries also provides more accessible income to many.

People have shared rides and houses before, but the matching, payment and review capabilities of products like Uber and Airbnb have made sharing easier and safer.

What makes up the sharing economy?

The sharing economy is the sharing of underutilized assets and services between individuals, typically using the internet to match buyers and sellers. These underutilized assets may include cars, real-estate properties, and food-delivery services.

Companies like Uber, Airbnb, and Lyft have accelerated the sharing economy; however, they have blurred the lines between commercial and personal activity. Making money has become less reliant on the employer-employee relationship, and more geared towards independently defined success.

Statistics Canada defines some of the key players:

Peer-to-peer ride services, such as Uber or Lyft: Services that connect riders and drivers through a mobile application that acts as an intermediary and processes the payment from the rider to the driver.

Private accommodation services, such as Airbnb or Flipkey: Services that connect travelers and hosts through a mobile application or website that acts as an intermediary and processes the payment from the traveler to the host.

*There are other kinds of interactions that make up the sharing economy, like food delivery services; however, we are focusing on private accommodation and transportation services because they have generated the greatest discussion in the West today. Traditional transportation and accommodation industries are facing stiff competition by companies like Airbnb and Uber that have aggressively cut into their market share. Food delivery companies, like Winnipeg based, Skip the Dishes are not as disruptive. Delivery drivers have not been replaced, even though the model that they work in has changed. Restaurants still benefit from food purchases – they just no longer deal with delivery costs.

What’s the impact on the West?

Sharing economy services are becoming more relevant in the four western provinces, especially Airbnb and Uber.

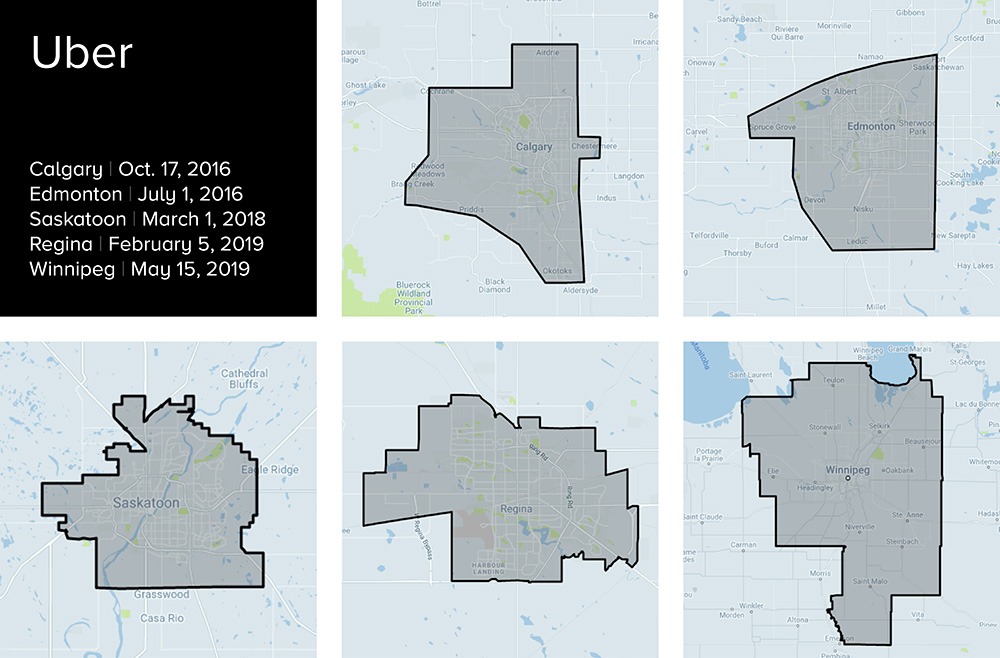

When did Uber touch down in the West?

Uber now operates widely across the West

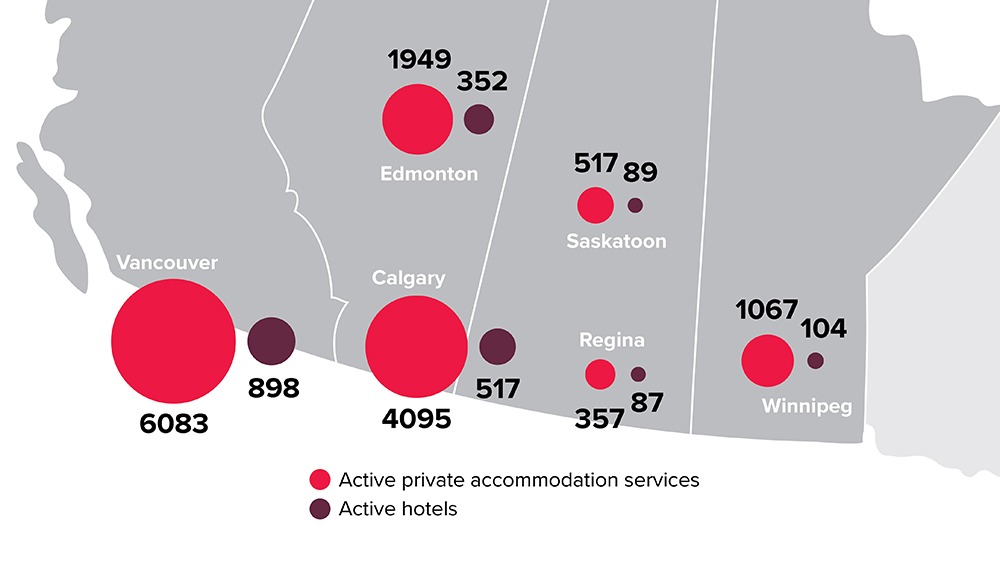

Airbnb growth in the West:

Canada represents one of Airbnb’s top markets in the world, and Western Canada is a significant part of this – the major cities across the West offer far more Airbnb options than hotel options. This has been a remarkably rapid change – Airbnb hit Canada in 2014 and within one year took up 10 per cent of the total accommodation supply, rising to 18 per cent in 2016.

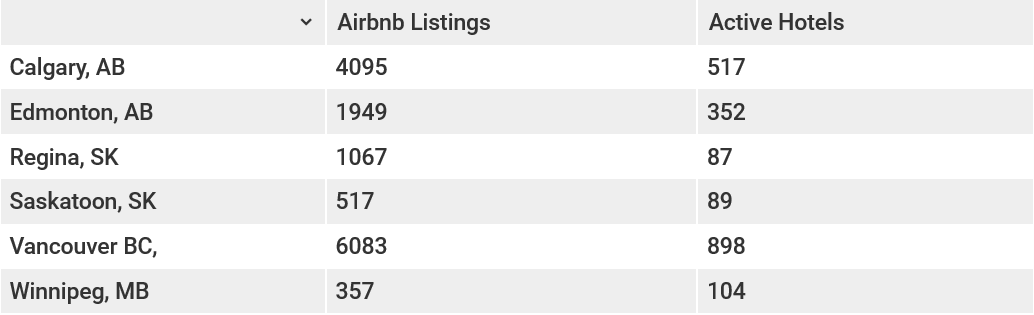

Comparing Airbnb to the hotels in the West as of July 2019:

Data retrieved from AirDNA and Expedia

The provincial breakdown

British Columbia: Airbnb has been operating in B.C. for almost 4 years now, and ride-sharing services are expected to touch down by Fall 2019. The regulation path for B.C. has been driven by the goal of leveling the playing field of these competing industries.

Alberta: Both Airbnb and ride-sharing services are in full swing in Alberta. In 2016, Calgary tried to heavily regulate Uber through a strict bylaw that would require Uber to pay an annual licensing fee of $1,753 and a fee of $220 per driver. After facing stiff opposition, this regulatory change was cancelled and Calgary has embraced the benefits of the sharing economy and is following the trend of inevitability; however, regulatory challenges still exist when it comes to ensuring multi-party protections.

Saskatchewan: The sharing economy was recently introduced to Saskatchewan in 2019. The Saskatchewan government sees nothing wrong with a little competition, as long as regulations ensure safety and fairness. Saskatchewan government minister Joe Hargrave, who is responsible for Saskatchewan Government Insurance, has expressed that that the sharing economy is healthy for the nature of competition and that Uber is “like opening another restaurant.”

Manitoba: While the sharing economy is relatively new to Manitoba as of this year and represents one of the less dominant provinces in the discussion of the sharing economy, future growth is expected. Within four months of Uber’s operation in Winnipeg, 29,616 unique users opened the Uber app to look for a ride.

The challenges & opportunities

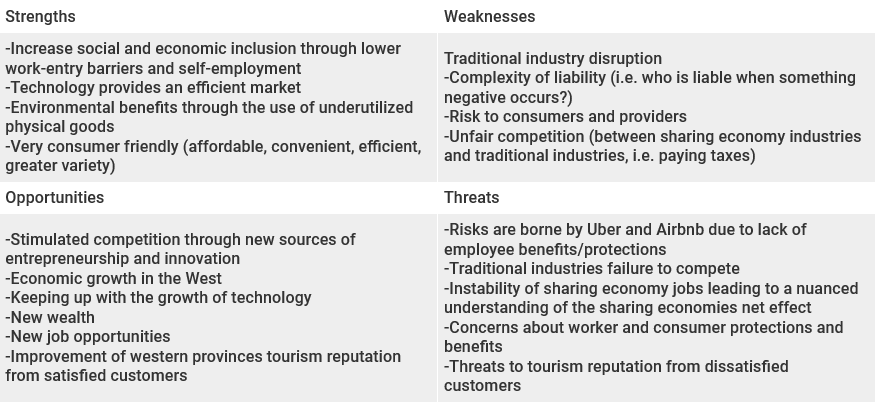

The blurring of personal and commercial activity has led to unclear regulation paths and increased risks for both those participating in and those competing against this technologically charged economy. On the other hand, although the sharing economy has seen tremendous growth – regulation may be able to help the western provinces reap the benefits of this growing industry, while protecting those who are vulnerable to it.

What are the social and economic impacts of the sharing economy?

What comes next?

The sharing economy is inevitable and

will continue to disrupt industries that Canadians rely so heavily on. This disruption,

along with the protection of consumers and service providers, give

policymakers and regulators even more reason to closely scrutinize the

industry.

What should policy and decision-makers strive for?

The nuanced nature of the sharing economy’s invasion in the West makes balancing disparate interests – consumer, employee, sharing economy companies and traditional companies – difficult. That being said, the western provinces should work towards:

Maximizing the benefits of the greater flexibility and lower work entry barriers provided by new business models, while addressing the risks that currently accompany many forms of the gig economy.

Are the sharing economy services under-regulated or are traditional industries over-regulated? Expect more work from CWF on this front in the future.

Taylor Blaisdell is a policy intern at the Canada West Foundation