Have you ever watched a TV show and felt that it could be reality in the not-so-distant future?

Or watched a presidential race and wondered if it is secretly a reality TV show? (But let’s leave the latter for another time.)

There’s a new show on Netflix called Occupied and it brings together current environmental and energy issues in a way that’s just close enough to reality to be truly thought-provoking (if not eerie).

Let me set the stage: Following a devastating hurricane blamed on climate change, Norway elects a Green Party. To live up to its lofty environmental promises, the government soon ends all oil and gas production in the country. The move comes at a turbulent time in energy geopolitics. The United States has achieved energy independence and withdrawn from NATO; the Middle East, meanwhile, is caught up in political turmoil that has slammed oil production. The EU – denied access to Norwegian oil and desperate for the stuff – turns to Russia to initiate a so-called “velvet-glove invasion” to occupy Norway and restore production.

The fictional show takes a number of intense (and surreal) turns but it also gets at a striking question: Is the idea of ending all oil-and-gas production really that far-fetched? The conversation on decarbonization by 2050 is well underway. With governments looking at energy efficiency and how to exist in a low carbon world, we can’t afford to be complacent. But a successful strategy shouldn’t be radical and based on bad economics. We will be there in 2050 to live with the consequences of these actions.

Can the world actually end all fossil fuel consumption by 2050?

Sometimes we forget how vital energy is to our high standard of living in the developed world. Since the industrial revolution, energy consumption (and access to cheap coal, gas and oil) has been a driving force for greater prosperity. In Canada, for instance, lights would go out in Ontario and Quebec’s factories, and homes would freeze without TransCanada’s mainline pipeline.

As the global middle class increases, the global demand for energy will increase as people acquire more cars and appliances. We need to find a way for a strong economy and a sustainable environment to go hand in hand. Targets have the potential to spur some activity. Aspirational targets without a concrete roadmap, however, are not helpful.

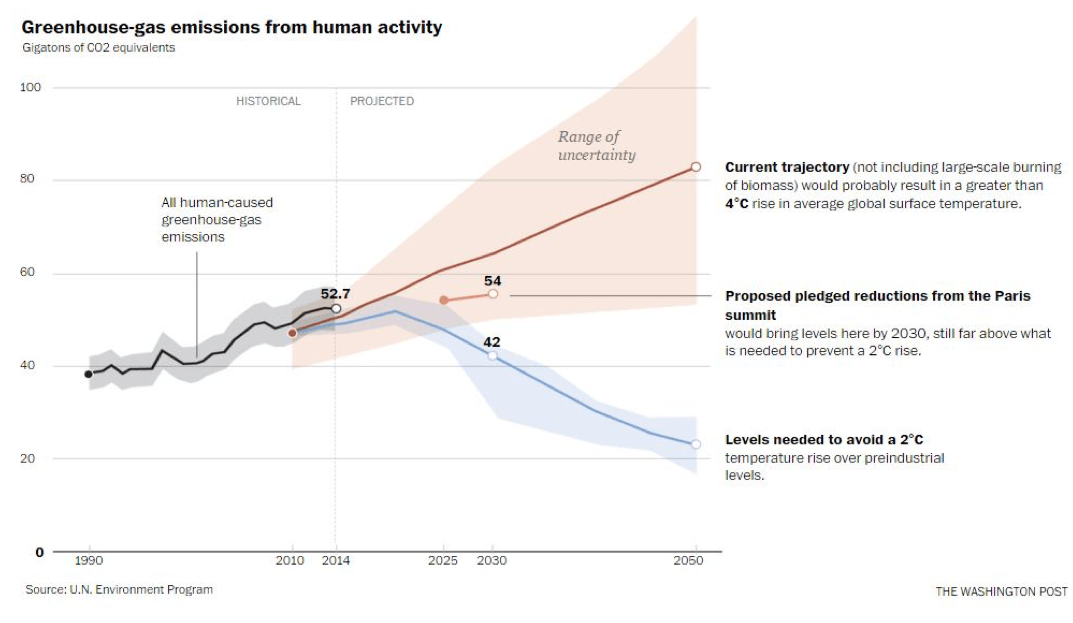

The world has seized on a target of limiting the rise in global temperatures to no more than 2 C higher than pre-industrial levels. If all countries meet their pledged emissions reductions, however, the world will still be 12,000 Mt short of what is needed to meet the target.

To put it another way: It would take eliminating ALL emissions (2014 levels) from Africa, the Middle East, South, Central and North America to close the gap.

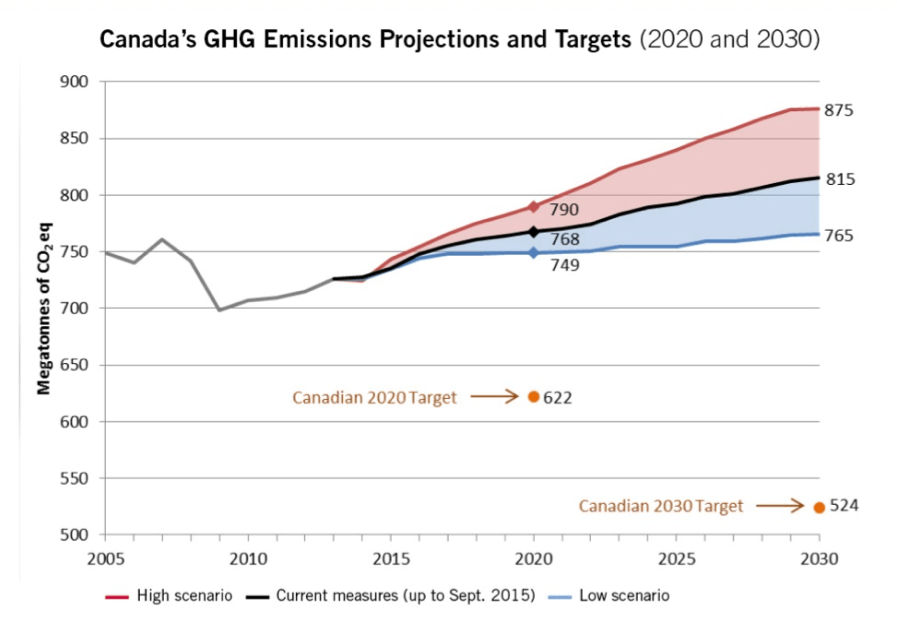

In Canada, policy-makers are in a tough situation, with aggressive emissions target in a delicate economic climate.

Source: Environment Canada

The Canadian government’s 2030 emissions target is 524 Mt (30% below 2005 levels), which is 0.97% of the pledged global emissions in 2030. Even with the low growth scenario for Canada’s GHG emissions and taking into account Alberta’s new climate plan (which plans to achieve a 50 Mt reduction by 2030), we are 190 Mt away from our 2030 target. Remember, this is the Canadian target of 30% below 2005 levels; not even what is needed to achieve the global 2 C target.

Here’s where it gets even more complicated.

One further calculation[1] shows that for Canada to reach the 2 C global target, our country would have to reduce emissions to 407 Mt by 2030 – a drop so massive the number falls off the bottom of the chart! Think of it this way: To have any hope of meeting the target would take Canada eliminating all current emissions from Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada – in less than 15 years.

Pressure is growing on governments to deal with climate change in an environmentally and economically smart way and we know we need to do more. But as commendable and ambitious as these efforts are – the sheer size of the task is daunting. It raises some tough questions. How far are we willing to go to reach the magic number? Do we want it at the expense of cheap transportation, reliable power and goods?

Television shows such as Occupied that take these questions to the extreme make for entertaining viewing. But back in the real world, we need to be realistic about our expections and find practical ways to meet our ambitious goals without collapsing our economy or ruining our standard of living.

– Shafak Sajid is a policy analyst

[1] 0.97% of 42,000 Mt = 407 Mt