A dispute coming to a head between China and Canada is threatening to put the western provinces’ $2.6 billion canola export industry through the wringer just as harvest starts to come in.

After years of unsuccessful negotiations between China and Canada, western canola exporters face the possible loss of their second largest export market after the U.S.

China is currently sitting on record canola oil reserves, estimated at six million tonnes, giving China leverage to push its demands. That the Canadian prime minister happens to be coming for a visit to “re-set” the relationship is also fortuitous timing for China to make a not-so-subtle point about the power balance in a new relationship.

The dispute between Canada and China is focused on dockage – organic debris in canola that is not canola. China is putting in place a new policy September 1 that requires shipments to contain just 1% dockage, down from 2.5%

China is claiming that the dockage has the potential to spread blackleg fungus disease to Chinese canola crops.

Blackleg is a disease caused by fungus that can dramatically reduce the yields of a canola crop if infected. It typically infects a canola crop by living in the stubble from the harvest the year before; it can also be spread for several kilometers through wind and rain, and there is a small possibility that blackleg can travel in infected canola seed.

Essentially, this is a scientific question on which Canadian and other impartial scientists disagree with the Chinese food safety authority. The existing research shows that there is no clear connection between dockage and the spread of blackleg. The Canola Council of Canada has said that the research that has been done on this has been in conjunction with Chinese authorities and by independent scholars. Significantly, Canadian canola is primarily shipped to canola processing plants in China that are not near actual canola crops. This ensures that already low probabilities of blackleg contamination are much lower still.

A few canola producers already spend the extra dollars to achieve the higher standard (which is higher than that of our other customers). However, the Canola Council of Canada argues that Canada simply will not be able to meet the 1% dockage standard given the time frame and additional cost required to achieve it. The Canadian export grain handling system was not designed to operate with the equipment required to clean the canola to that extent, while at the same time being able to process grain with the efficiency and speed required of our large volumes of grains.

China’s canola oil reserves

From 2009-2015, China had a canola oil reserve program; this program bought canola from Chinese farmers at much higher prices than world prices. The oil processed under this program was placed into reserves. The program ended last year, because China had amassed a reserve of six million tonnes of canola oil. Last year, the Chinese government sold approximately 600,000 tonnes of oil, but that still leaves several millions tonnes of oil in reserves that are costly to maintain.

The fact that the dispute over blackleg started in the same year as the Chinese domestic canola buying program should give pause.

Canola consistently goes for a high price. The high, stable prices (which result from high, consistent demand) combined with the right growing conditions, are why canola is grown so extensively in western Canada. Canada is by far the largest producer of canola in the world, producing 41% of the world’s total. Australia is a distant second, producing 12% of the world’s total. Some of Australia’s canola is exported to China, but China gets the vast majority – 88% – of its canola from Canada.

A big deal in western Canada

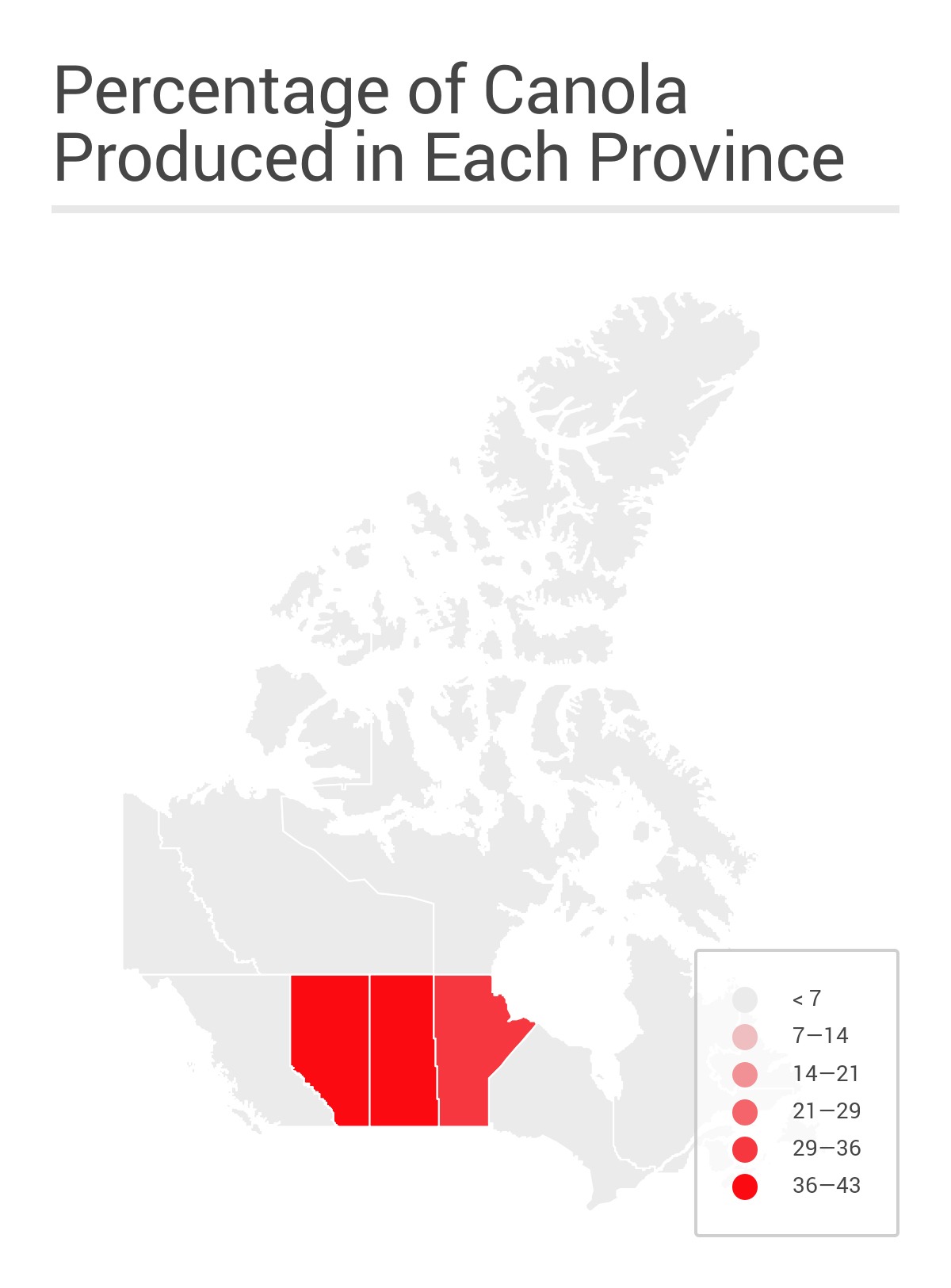

For western Canada in particular, this dispute matters. In 2015, the western provinces produced more than 99% of Canada’s entire canola harvest. Canola has been king in the West since shortly after its invention in Manitoba and Saskatchewan in the mid-1970s. In 1976, canola accounted for just 7% of the total crop cash receipts in the western provinces. In 2015, that number rose to more than 36% of total crop cash receipts in the west, or roughly $8 billion.

The canola industry carries impact beyond the cash that it brings in. In 2013, the canola industry contributed more than 249,000 jobs, in addition to the billions of dollars that it brought into the Canadian economy. Virtually all of this income and employment is dependent on export market. In 2013, Canada exported 90% of its canola to other parts of the world – and almost half of that went to China. With this in mind, it is clear that it is very important for the Canadian and Chinese governments to come to an agreement about dockage and its potential to spread blackleg, otherwise the viability of the Canadian canola industry may be in jeopardy.

Eliminating the market for Canadian canola will drive its price down as Canadian producers will have to find new markets for their crops and compete not just with other producers, but other products such as soy and corn in the oilseed markets.

Playing the long game

The sudden reemergence of the blackleg debate raises serious questions about whether the move is part of a longer play from China to force down the price of canola. China’s efforts to grow its own canola (through the canola oil reserve program launched in 2009), save costs and reduce its reliance on exports, was scrapped in 2015. Another way for China to spend less on canola would be to force lower prices from its main source: Canada. That is why the timing of this debate over blackleg is significant. It was only a few months after the domestic buying program was shelved that the blackleg debate was renewed.

When a harvested crop has more dockage in it than the minimum, the price paid for that crop is lower, because it is deemed to be of lower quality. Because China relies so heavily on canola imported from Canada – and we rely so heavily on China to buy it – Canadian canola will still be sold to China. However, if the 1% dockage rule sticks, less will be paid for it. Down the road, China stands to reap massive cost savings for its canola imports.

Walking a fine line with China

The danger in all of this is twofold. In the short term, a sudden loss of exports to China will do damage to Canadian canola farmers. This could have the added effect of further entrenching negative feelings seen in polling in the prairies toward China toward a trade agreement and could poison the waters for years to come. The second danger is that, faced with political unrest in the prairies, Canada overreacts in the other direction and capitulates too quickly.

For a relationship that is the next big thing for Canada and for western exporters, setting the framework for constructing this relationship is of fundamental importance. We need to step back, pause, and make sure we handle this right.

The path forward is one that should be familiar to Canadians: firm, persistent and preparing to endure short-term pain for longer term gain. This is how we not only survive but thrive in our relationship with the United States. From softwood lumber to country of origin labelling, we have seen this game before. Canada enjoys and prospers from more than $2 billion in trade crossing the border every day with the world’s largest and richest market. But that is little comfort to farmers or businesses who face severe losses or bankruptcy when the Americans suddenly change the rules of the game.

For the federal government, the timing on the dispute is inconvenient. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will arrive in China on August 30 – two days before the 1% dockage rule comes into effect – with the aim of exploring the future of a free trade deal with China. Canadian government officials have said the goal of the trip is to “restart the relationship” between the two countries. China has said that it will try to keep the issue of canola off the agenda entirely, as it is “a scientific matter that should not be on the agenda of the official visit.” Not a warm start to this new relationship.

Building a healthy trade relationship with China is essential for the future of the Canadian economy. However, the canola controversy is only one example of the bumps along the way. The federal government must walk a fine line between protecting short and long-term Canadian concerns in establishing this relationship with China.

China has often been touted as a balance or antidote to over dependence on the US market. In reality, it is looking more like a replication of our relationship with the Americans. Western exporters know the benefits of the pains of that relationship. Whether that is a comfort or a torment, it is reality.

– Carlo Dade is the Director of the Centre for Trade & Investment Policy and Sarah Pittman is a research intern at the Canada West Foundation