In Paris for the UN Climate Conference, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced, to much fanfare, that Canada is back.

Indeed, the Trudeau government reaffirmed Canada’s aggressive climate targets (30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030) while intimating that Canada will do more.

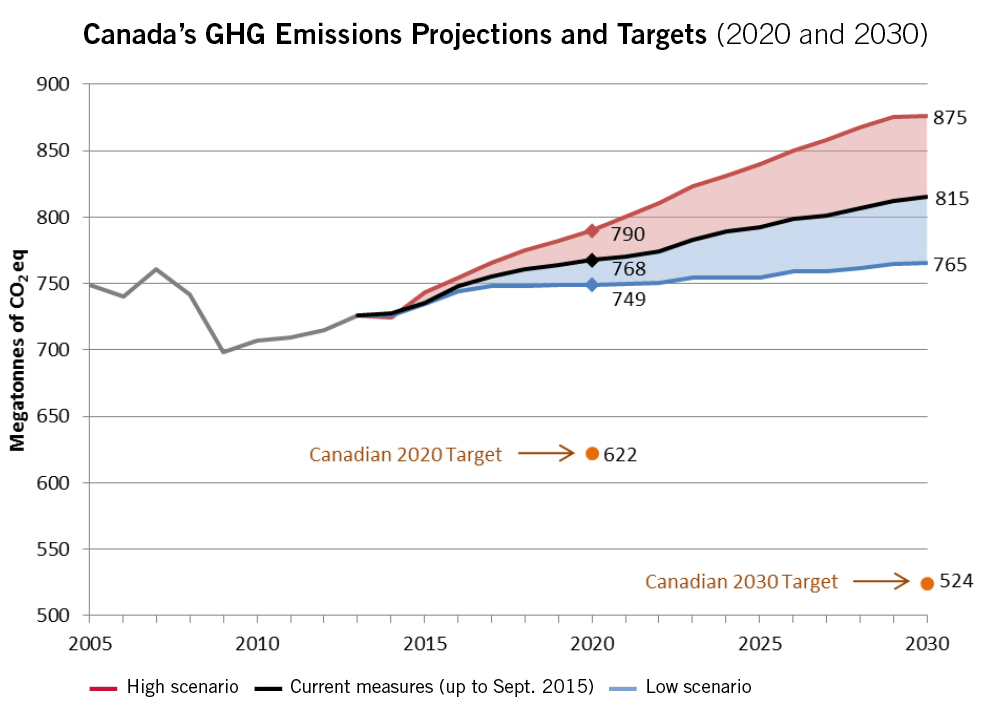

To meet the 2030 target, Canada will have to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 240 megatonnes (MT). This is no easy task; it is the equivalent of eliminating all GHG emissions from Ontario, Atlantic Canada, Manitoba and the Territories.

If Canada was to do its share to ensure that global temperatures do not rise 2C above preindustrial levels, we’d have to find an additional 120MT in reductions by 2030. Eliminating the oil sands would only net an additional 70MT of reductions.

This Environment Canada chart tells the story.

There is little doubt that the new government is keen to meet Canada’s Paris commitments. Trudeau has announced a First Ministers’ process designed to create a Pan-Canadian Climate Strategy and Environment Minister Catherine McKenna has pursued the issue with vigour. Yet, the prevailing view in western Canada is that Trudeau and McKenna will blink before forcing the economic pain that would be required to meet Canada’s targets.

Maybe.

But what happens if they don’t blink? Which provinces will shoulder the burden of meeting the targets?

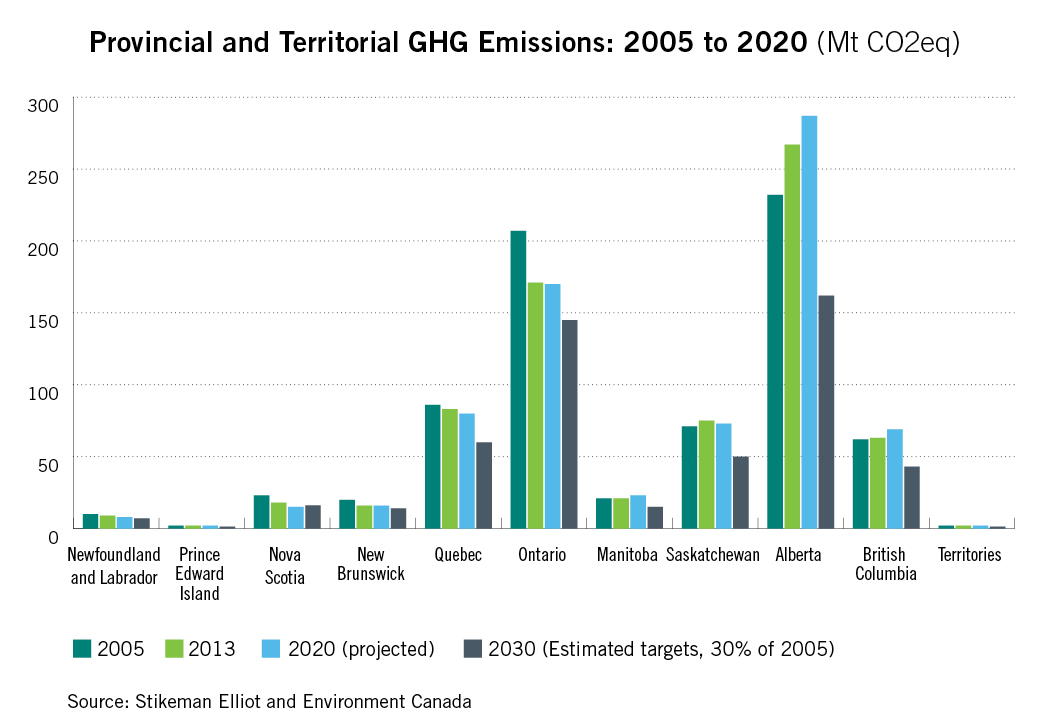

An old Japanese proverb comes to mind: The nail that sticks up gets hammered. This chart, which shows GHG emissions by province, makes it pretty clear which nails stick up.

If Trudeau wants to meet his aggressive GHG targets then Alberta will get hammered. There is no realistic path that doesn’t include massive reductions in Alberta. Ontario will have to do more, too (but the Ontario government doesn’t seem to mind hampering its economy). Saskatchewan and British Columbia (especially if LNG actually happens) will also be pressured to do more.

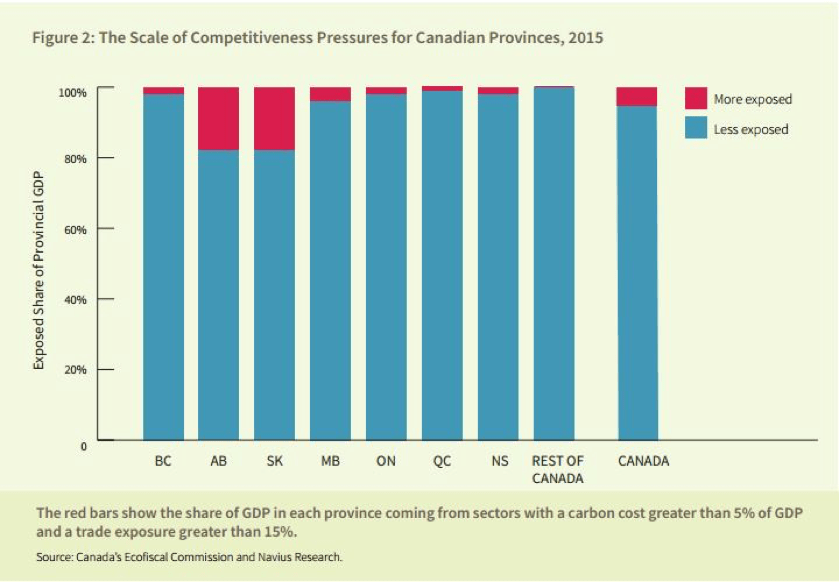

Alberta and Saskatchewan, in particular, need to remain vigilant. The economies of these two prairie provinces are more energy intensive and trade exposed.

This means that Alberta and Saskatchewan are more vulnerable to carbon pricing because they compete with jurisdictions that tend not to price carbon. Put simply, Saskatchewan cares if North Dakota and Texas price carbon (hint: they don’t), not if P.E.I. and Ontario do. If Saskatchewan makes itself less competitive vis-a-vis North Dakota then carbon emissions, jobs and GDP will simply shift across the border. We would be responsible for increasing global emissions while we are shedding jobs – this should satisfy no one. No wonder Premier Brad Wall is up in arms.

The Alberta government (and the oil patch) seem convinced that the combination of Alberta’s shiny new climate strategy (which made Trudeau look great in Paris) and ballooning deficits in Alberta (and Ottawa) may keep Trudeau at bay. They could be right.

But here’s the thing: If Trudeau is serious about Canada meeting its targets, there is no credible path that doesn’t go through the prairies (or, more accurately, through the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin). Premiers Brad Wall and Rachel Notley would be well-advised to bury the hatchet soon.

They might find inspiration in the example of two of their predecessors: Allan Blakeney (NDP Premier of Saskatchewan, 1971-1982) and Peter Lougheed (PC Premier of Alberta, 1971-1985). They succeeded in putting their party differences aside for the good of their provinces.

– Trevor McLeod is Director of the Natural Resources Policy Centre