Churchill’s uncertain future—Part 1

The Port of Churchill – the only Arctic port in Canada – closed “for the season” but quite possibly for good on Aug. 8.

It is widely assumed that the owner of the port, Denver-based OmniTRAX, will not reopen it, although the company has said it will consider opening for the 2017 shipping season.

In the northern Manitoba community of Churchill, nearly one in 10 residents was employed by the port. As Churchill ponders its economic future in the wake of the closure, it is worthwhile to examine the deepwater port’s history and place in the community.

The Port of Churchill was constructed in the 1930s to export commodities from western Canada. It became both an access to market for the Prairies, and a boon for the northern Manitoban economy. The community of Churchill, historically with a population of around 1,000 people (although in more recent years closer to 750) typically saw about one-tenth of its population working at the port.

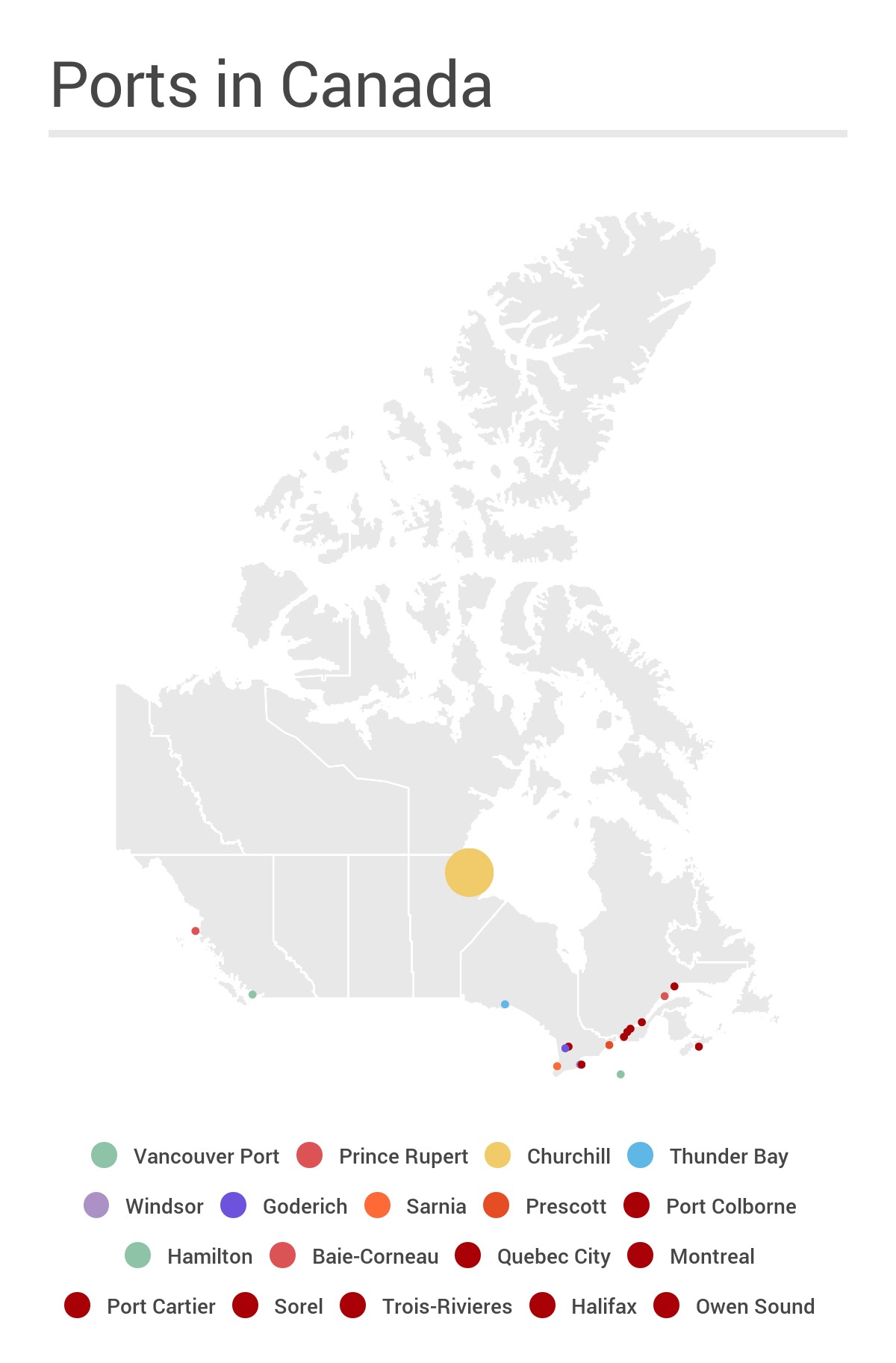

The Port of Churchill is unique: It is the only Arctic port, and the only deepwater port in a prairie province. Churchill, in the northeast corner of Manitoba on the Hudson Bay, is reachable by air, rail and sea (some months of the year) – but not road.

The port received its grain shipments via the Hudson Bay railroad, which connects Churchill to the rest of Manitoba. The railroad is built on permafrost. When the permafrost thaws, it causes the track to warp, meaning that the rail line requires constant, expensive maintenance. In turn, this means that the Port of Churchill shipping season has been limited to when enough ice melted to make the trip feasible; this typically begins at the end of July and lasts three to four months.

The Port of Churchill had some advantages, too, particular that it was cheaper to ship grains from the prairies, especially Saskatchewan and Manitoba, to Churchill than any other port. The port also offered a quicker trip to Europe than the ports in the St. Lawrence Seaway. For example, it takes 14.42 days to export grain from Thunder Bay to Murmansk, Russia, whereas it takes 11.42 from Churchill.

Through the decades, the port has had a complicated relationship with the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB). The CWB was established in 1935, with the goal of controlling wheat prices to help farmers survive during the Great Depression. In 1965, it became a permanent committee. The CWB had a solid grip on the Canadian wheat market until the mid-2000s, when the Conservative government under Prime Minister Stephen Harper began dismantling the CWB’s monopoly. This occurred Aug. 1, 2012.

Through the decades, the port has struggled with weather, insurance rates and the economy; yet, it was the end of the CWB monopoly that signaled the beginning of the end for the Port of Churchill. The Manitoba port had seen consistent traffic for most of its history. This was partially because the Canadian Wheat Board had the ability to ship grain to whichever port it chose, and it consistently used the Port of Churchill. When the CWB lost its monopoly, the port lost its biggest customer.

In an attempt to counter the expected drop in grain shipments from the Port of Churchill, the federal government started the Churchill Port Utilisation Program (CPUP) in 2013. The five-year, $25-million program was set up to provide subsidies to companies that shipped their grain through the Port of Churchill. Initially, the subsidy was $9 per tonne shipped to Churchill; it was increased to $9.20 in 2014 and recently, it was increased to $12/tonne. This represents a significant portion of the cost of transporting grain to Churchill.

Throwing Money at the Problem

The CPUP is not the only subsidy program that has been provided to the port. Between 1977-1994, provincial and federal governments spent $150 million on the Port of Churchill. That is roughly $9 million in subsidies per year.

In 1997, OmniTRAX purchased the port. The subsidies continued. In addition to the $25 million from CPUP, the provincial government contributed seven-figure subsidies.[1] In 2015 alone, there was about $6 million in subsidies for the port. For perspective, if the subsidy was divided among the approximately 90 employees who worked there last year, that is equal to roughly $65,000 each.

The millions of dollars of subsidies have not been enough to keep the Port of Churchill afloat.

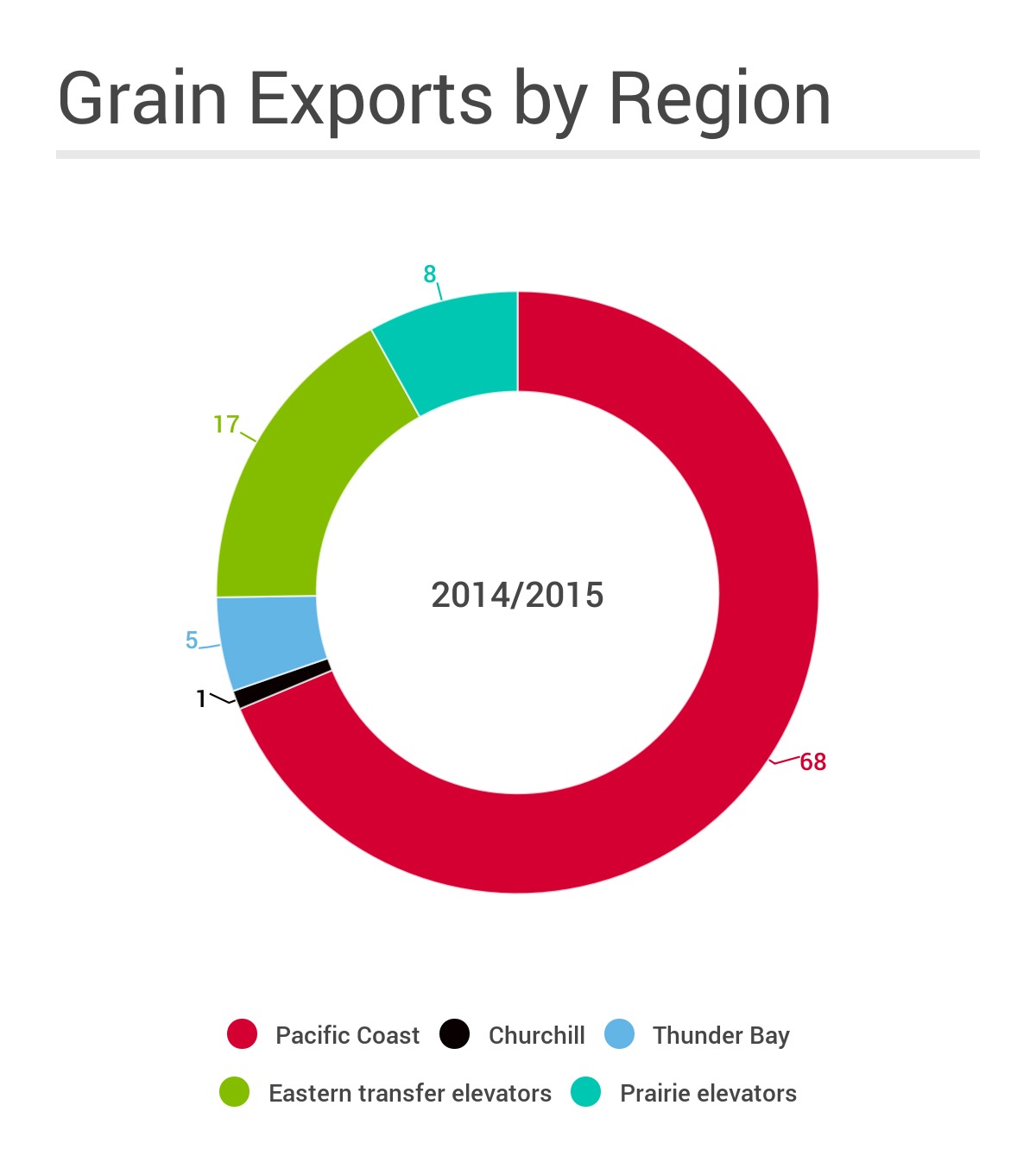

Recently, the grain that was moved through Churchill that was typically about two per cent of all grain exports from Canada dropped to less than one per cent.[2]

Meanwhile, exports from the ports of Vancouver and Prince Rupert have risen significantly. This indicates that increasingly more grain is exported from the West out of the Pacific, rather than the Arctic.

It’s not over until it’s over

Stakeholders in the Port of Churchill and those from the community of Churchill have been scrambling for a solution to save the grain-exporting capabilities of the port.

In December, it was reported that an undisclosed First Nations group purchased the port, although little has been said about the deal since then.

Some, including the mayor of Churchill, have called on Ottawa to buy back the port. The federal government has since indicated it is looking into possible solutions, but has offered few details.

The grain shipping days from the once-great northern port are over. Yet Churchill itself remains an important community. There is much it can do to harness the benefits of its position both in a prairie province and as part of the Arctic. These possibilities will be explored in Part 2 of the Port of Churchill series.

– Sarah Pittman is a research intern

[1] No one seems to be really clear about what the exact amount is—it was in a confidential agreement signed by the previous NDP government.

[2] Canadian Wheat Commission.