The Global Middle Class and COVID-19

by Taylor Blaisdell

Growth of the Global Middle Class (GMC) has been a focal point for policy making on the Canadian, but particularly the Western Canadian, export agenda in recent years as both an opportunity and a challenge. Notably, it is a foundational part of the federal government’s export strategy and been aggressively embraced by the agricultural producer community.[1]

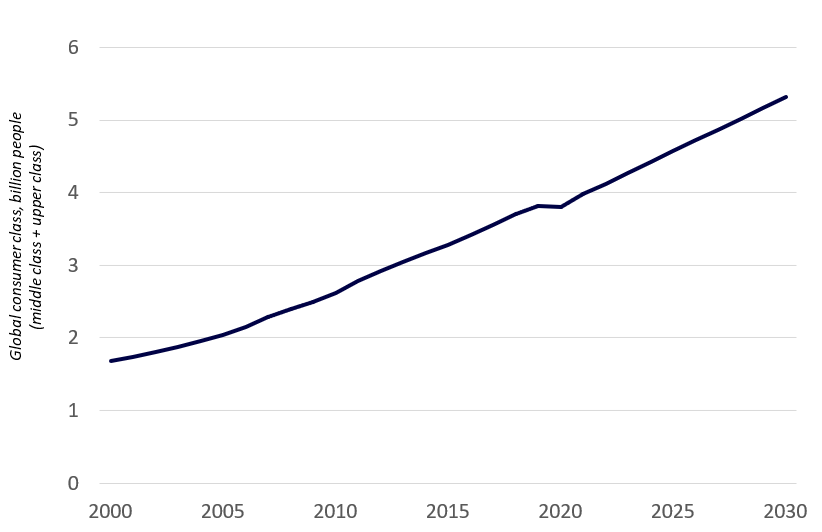

Part of the reason for this focus is that expansion of the GMC had been virtually uninterrupted in recent years and was almost universally expected to continue, but it hit a bump in the road because of the pandemic. In this update, we examine how big that bump actually is, whether it represents a delay or a reversal, and what future growth projections are for the Global Middle Class. Crucially, we also look at how Western Canadian export markets—predominantly the ag sector—can identify new opportunities and challenges beyond the pandemic.

As global markets shift and transform, so does Western Canada’s potential for becoming a global leader in agri-food—making it worthwhile to keep up with overseas markets as the pandemic continues to alter the economic global stage.

We wanted to see how the COVID pandemic has affected the GMC. We’ve reviewed available reporting and data on five countries – China, India, Mexico, Indonesia and Brazil – and highlighted key data, events and projections on the topic of the Global Middle Class. These markets were chosen because they are major trade partners to Canada or announced targets by the federal government for new trade agreement negotiations.

GMC defined

Definitions of the Global Middle Class vary across institutions and countries and quantifying this group is difficult. It is important to differentiate between how GMC is defined versus how it is measured.

At CWF, we define the members of the Global Middle Class as individuals who have enough disposable income, and confidence that this income bump is permanent enough to regularly consume more and consume higher quality products, including foreign products.

Between 2011 and 2019, the global middle-class population increased from 899 million to 1.34 billion, averaging an annual rate of 54 million people.

The technical measurement developed by the Brookings Institution in 2010 and adopted by the World Bank and most international business publications is helpful here: GMC status refers to those individuals with an income between US$10 – US$100 per day at purchasing power parity.

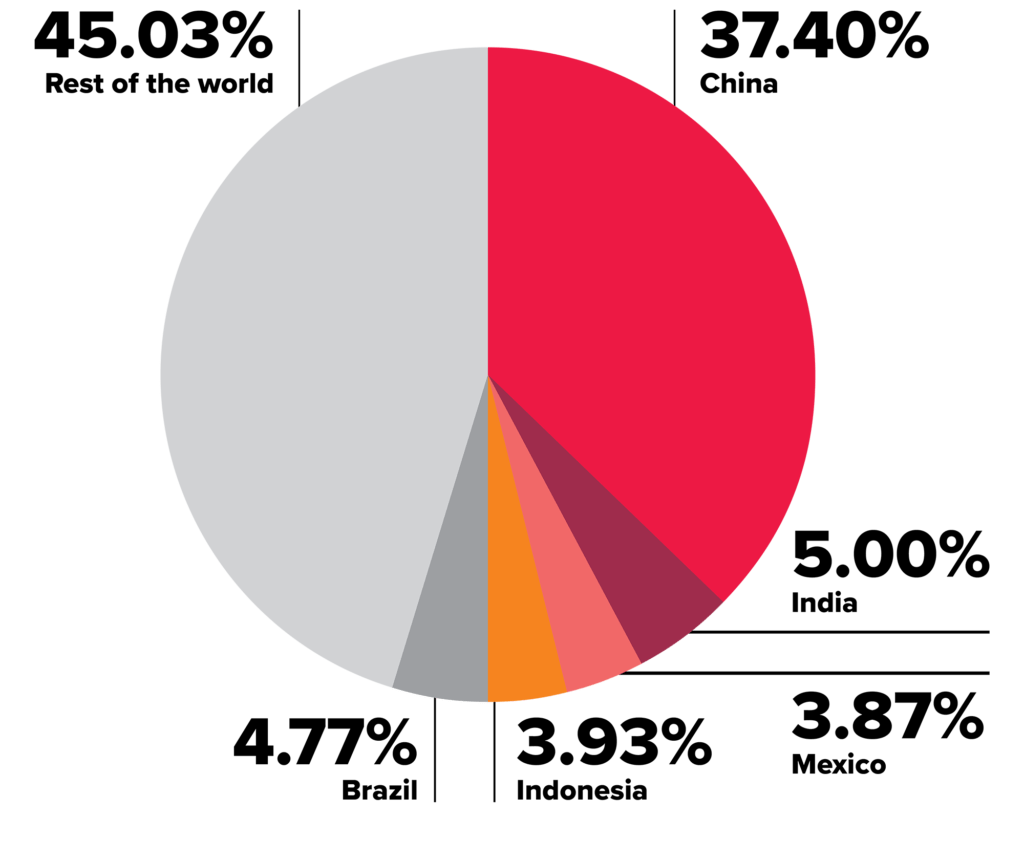

The pie chart below represents GMC proportions of our focus countries in relation to the rest of world. According to Pew Research, in 2021 the size of the Global Middle Class was approximately 17.1 per cent of the world’s population—1.34 billion— back to where it was in 2019.

Per cent of the World’s Global Middle Class in 2021 – 1.34 billion

GMC of countries of export importance to Canada

Size of GMC (2021) | GMC as a % | FTA with Canada | |

China | 493 million | 35.2% | No |

India | 66 million | 4.78% | Target |

Mexico | 51.2 million | 39.2% | Yes |

Indonesia | 52 million | 20% | Target |

Brazil | 63 million | 29.5% | Target |

Source: Canada West Foundation

China

COVID

In December 2021, COVID-19 cases started to increase in Mainland China. In the first week of the month, 78 new infections were being reported daily despite the country’s impressively high vaccination rate. As of December 8, 2021, 91.8 per cent of the Chinese population had been fully vaccinated.

THE ECONOMY

The economic impact of the pandemic in China has been starkly different from that of other countries and figures show that China was the only major economy that saw growth in the year 2020. While strict nationwide lockdowns and virus containment measures stalled production temporarily in 2020, China’s overall experience has been one of resilience and growth.

THE GMC

The majority of the Chinese population reside in middle and upper-middle income tier, with much of China’s middle class expansion taking place in mega-cities like Shanghai, Beijing and Shenzhen. Pew Research reports that between 2011 and 2019, China’s GMC grew by 247 million people to a total of 504 million, which represents 37 per cent of the world’s total GMC. Pew Research also estimates that during the pandemic, roughly 10 million people fell out of China’s GMC. This modest decline (1.98 per cent of China’s total GMC population) and continued economic growth in China have set the country’s GMC projections to remain on track. Based on these figures, rapid growth in China’s middle class will continue to shape future global production and supply chains and pose opportunities and challenges for high-income economies, Canada’s included.

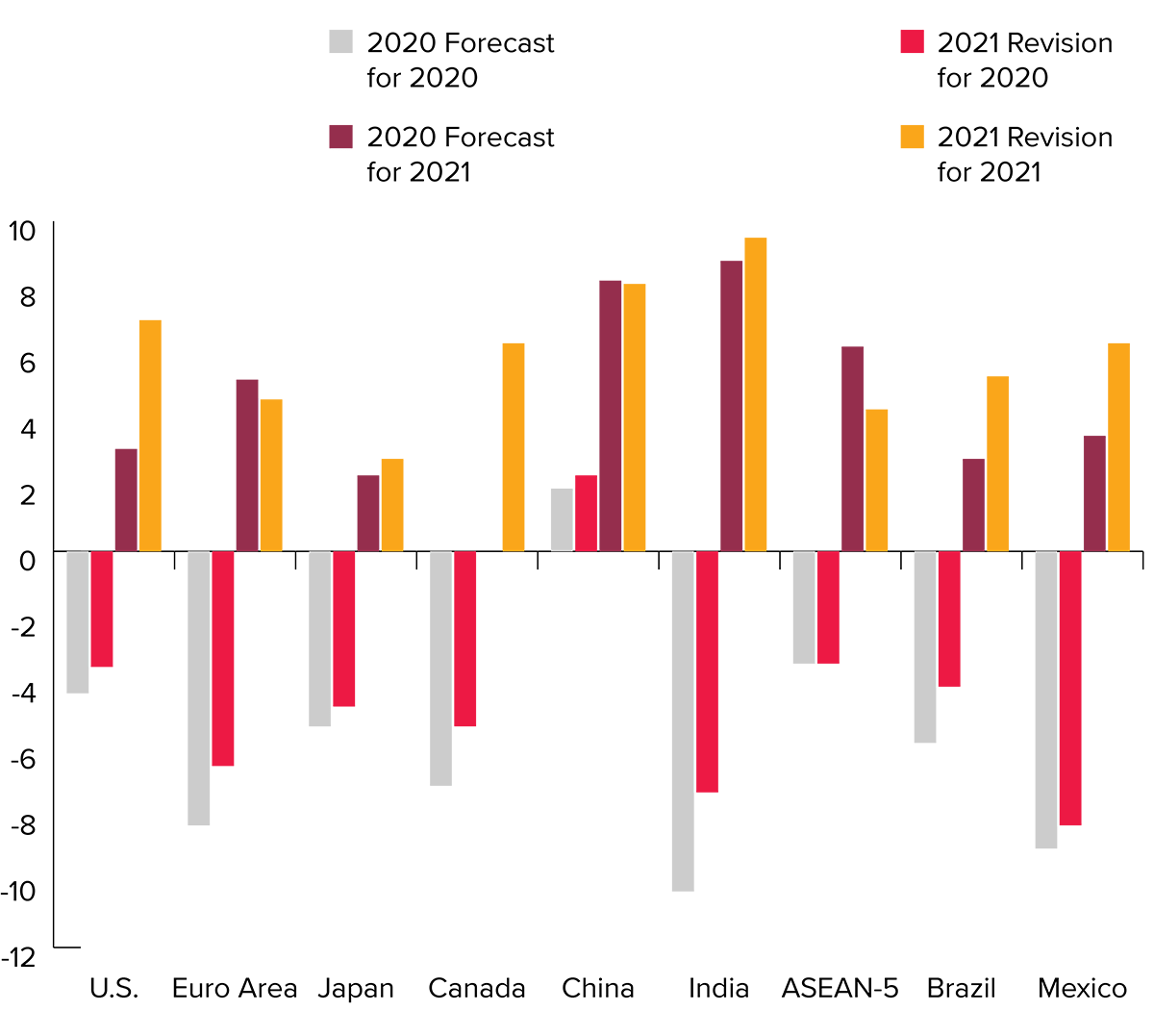

China Economic Performance During COVID

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, 2020, 2021

India

COVID

The first case of COVID-19 in India was discovered on Jan. 30, 2020 with infection rates peaking on May 8, 2021. The country’s second wave was largely caused by the movement of infected migrant workers commuting from urban centres back to their rural villages. As of December 8, 2021, only 47.3 per cent of the country’s population had been fully vaccinated.

THE ECONOMY

Although case numbers hit record highs in the second wave, economic damage was greatest during the onset of the pandemic, with stock markets in India posting a contraction of 7.3 per cent between 2020 and 2021, their worst crash in recorded history. The rebound has been impressive and in its Monthly Economic Review for April 2021, the Indian Finance Ministry noted that economic activity had learned to “operate with Covid-19.”

THE GMC

As a result of the pandemic, 32 million Indians were pushed out of the middle class and back into poverty, subsisting on US$2 or less per day. These 32 million account for roughly 33 per cent of India’s GMC and 60 per cent of the total global contraction of the middle class during the pandemic. The GMC decline was more significant in India compared to the rest of the world—mainly due to the lack of any sort of social safety net. Projections for the GMC in India are influenced by—and dependent on—pandemic recovery capacity and whether or not the pandemic brings long-lasting change to small business operations and middle-class employment. The shrinking middle class in India can be attributed in part to structural flaws in India’s growth model where stagnation was present even before the pandemic.

Mexico

COVID

The country’s first confirmed case of COVID-19 was in late February 2020 and within a month the country had surpassed one million confirmed cases. Mexico experienced its peak in daily infections on August 17, 2020 and numbers have been retreating as vaccination rates increase. As of December 8, 2021, 52.7 per cent of the population were fully vaccinated

THE ECONOMY

The onset of the pandemic was especially difficult for Mexico as a sharp fall in labor income created economic havoc with 73 per cent of the Mexican population experiencing food insecurity at the peak of the pandemic. By July 2020, in the midst of lockdowns, 85 per cent the working Mexican population lacked the equipment to work from home.

THE GMC

A large portion of the middle class in Mexico exists due to NAFTA, as jobs and more affordable products were brought to the country starting in 1994. Like other emerging markets, Mexico was seeing an expansion of its middle class prior to the onset of the pandemic. But in 2020, the pandemic pushed Mexico into its worst recession since the Great Depression and the economy shrank by 8.5 per cent. Combined with high rates of unemployment and sparse, limited government support, the fall from the middle class has become inevitable for many Mexicans. The World Bank estimates that roughly 4.7 million Latin Americans fell out of the GMC as a result of the pandemic.

However, like most of the other focus countries, continued growth of the GMC is expected in the future despite the impacts of COVID. In the next 10 years, the Global Middle Class in Mexico is forecast to grow by 20.1 million people and economists suggest its economy will become the fifth-largest in the world by 2050 primarily as a result of growth in its manufacturing and energy sectors. As the economy reboots, we can expect more Mexicans to re-enter the global middle class.

Indonesia

COVID

Indonesia was first officially exposed to the coronavirus on March 2, 2020. The daily infection peak was July 17, 2021 and the country is now seeing a decline in cases as vaccination rates slowly rise. As of December 8, 2021, 44.9 per cent of the population was fully vaccinated.

THE ECONOMY

As a result of China’s slowing economic activity in the early stages of the pandemic, Bank Indonesia cut interest rates by 25 basis points to 4.75 per cent. And in March 2020, for the first time since 2008, equity trading was halted. A slow pandemic response resulted 2.75 million Indonesians dropping below the poverty line. As a result, the country lost its status as an upper-middle-income country – a rank only recently achieved because of middle class expansion, infrastructure development, and foreign direct investment.

THE GMC

Despite this status setback, by 2030 the middle class in Indonesia is forecast to grow by 75.8 million people, surpassing Japan, Russia and Bangladesh and becoming the fourth-largest middle class in the world.

Brazil

COVID

Its first case of COVID-19 was confirmed on February 26, 2020 and the country experienced peak daily infections on June 22, 2021. Brazil was among the worst hit of all countries with a death toll of over 600,000 recorded by December 2021. Cases have begun to decline as vaccination rates increased with 75 per cent of the population fully vaccinated as of December 8, 2021.

THE ECONOMY

COVID-19’s impact led to a GDP drop of 4.1 per cent in Brazil by the end of 2020, the worst since 1990. In Brazil, 40 per cent of workers operate in the informal sector, meaning they typically lack access to employment benefits and pensions. As a result of the pandemic, unemployment increased by 14.6 per cent, leaving many Brazilians unsupported. Brazil’s social protections however, proved to be both proactive and effective.

THE GMC

According to the World Bank, 12 million people were prevented from falling out of the middle class, thanks to the country’s comprehensive social protection program. Brazil still saw significant shrinkage of the middle class, with 4 per cent of the tier falling into poverty. The drop is expected to be temporary with the middle class in Brazil forecast to grow by 20.6 million in the next 10 years.

Looking ahead

While the ‘bump’ in the global middle-class growth trajectory has devasted individual livelihoods and economic statuses, findings show that the overall impact of the pandemic on the global middle class has had little effect on future economic forecasts. Growth trends are expected to return to pre-pandemic rates in less than a decade. And while we do know that the global middle class is expected to experience continuous growth following the pandemic, we cannot say it will be equal across regions.

A COVID-19 bump in the road to a middle-class world?

The tale of China and India, in particular, are central to understanding for Canada’s GMC focused export growth plans.

Figures show that the middle class in India shrank by 32 million in 2020, while in that same year in China, the middle class shrank by 10 million. That change, however, is relatively small considering how large the middle class in China was before the pandemic—504 million people. For India however, the size of the middle class in 2020 was roughly cut by a third—dropping from 99 million to 66 million. India’s drop accounted for nearly 60% of the total global decrease of the middle class.

A return to growth of the GMC is, of course, tied to broader economic recovery. We have seen early signs of recovery slowed or temporarily reversed as new variants of the virus have emerged. The pandemic recovery of China has proven far more successful than that of India. As China sustained its economic performance and saw positive growth, India fell into a recession with negative growth of 9.6 per cent. While global middle-class trends are forecast to return to their pre-pandemic state, we must be aware that while some countries are moving in one direction, others are heading in the opposite.

In the near term, the better performance of the GMC in China versus the severe decline in India will inform thinking in Canada on the best tactics to diversify trade from China. In the longer term, looking to India may be an option but the country’s ability to respond to future pandemics will need to be evaluated. This pandemic response is a necessary lens for any new planning based on the rise of the GMC. The COVID pandemic has shown that growth of the Global Middle Class, once thought to be an unstoppable force, is anything but.

[1] Advisory Council on Economic Growth, ‘Unleashing the Growth Potential of Key Sectors’ (Government of Canada, 6 February 2017), https://www.budget.gc.ca/aceg-ccce/pdf/key-sectors-secteurs-cles-eng.pdf. Barton Forward: Optimizing Growth