Authors: Martha Hall Findlay and Marla Orenstein

Bill C-69 was introduced over a year ago. Currently before the Senate, it continues to be divisive. Elements of the bill have garnered support: increased transparency with respect to decision-making, additional opportunities for Indigenous participation, the introduction of regional and strategic assessments and the use of an early planning phase. These are all elements the Canada West Foundation supports.

However, there are serious concerns with the bill as drafted, which we share. (For detail, please see our prior work from February 2019: Bill C-69: We can get this right.)

We commend the Senate for being open to recommending amendments that could address some of these concerns. However, this still may not be enough. Our continuing analysis of the bill has uncovered several additional aspects that we believe to be extremely problematic. Each would open the door for project opponents to restart the court challenges process, setting every project back years.

The unintended consequences of losing this jurisprudence could be disastrous – and irreversible.

In this briefing note, we focus on four elements that threaten the established jurisprudence on the environmental assessment and project approval process:

• The role of the Governor in Council (GIC, or the federal Cabinet) given significant added requirements in Section 65(2) of the Impact Assessment Act (IA Act).

• The replacement of the National Energy Board (NEB) with a different regulatory body, and removal of the lifecycle regulator for project approval.

• The potential for a reference to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) to overrule duty to consult jurisprudence.

• The inclusion of broad, undefined terms that have not yet been reviewed and will require further interpretation by the courts.

This is not simply an academic issue. If the legislation “bakes in” elements that cause future decisions to founder, Canada faces years of unnecessary court challenges to iron out the issues – which will prevent important economic activity, which in turn will result in additional “fleeing” of future investment from major projects in Canada.

–

The problem of losing jurisprudence

Although much of the talk on C-69 is about regulatory timelines, by far the biggest cause of delays and uncertainty about projects has been court challenges.

The good news is that, over the past few years, major court cases have, finally, provided considerable certainty in terms of what is expected regarding both the project approval process and the duty to consult. In particular, the two recent recent Federal Court of Appeal cases, Gitxaala Nation v Canada (2016 FCA 187) (Gitxaala); and Tsleil-Waututh Nation v. Canada (2018 FCA 153) (TMX)¹ focused on these issues. Other than for the narrow maritime shipping scoping issue raised in TMX, these discussions have, in effect, endorsed the current National Energy Board (NEB) project approval process, as well as the GIC’s decision-making role based on the NEB’s reports.²

The current framing of the Impact Assessment Act (IA Act) changes the process sufficiently that this jurisprudence will no longer apply. Losing this hard-won jurisprudential certainty will allow court challenges to start back at square one – resulting in years more of delay in getting any major energy and other types of infrastructure built.

To be clear, our court process is a fundamental part of our democracy and system of regulations – and analyses of legitimate issues by the courts have improved our system. Unfortunately, in recent years, we have seen the system abused by those who object, on any ground, to any oil and gas-related project – to delay and, they hope, terminate projects. This is unacceptable for any kind of balanced approach to the Canadian economic and environmental priorities. Those who see court challenges as a way of delaying or stopping energy projects will start all over again, causing more delay, leading to years of additional and unnecessary delay for any major pipeline or any major electricity transmission line, and a whole new climate of uncertainty for investment.

An added twist: Some environmental activists may cheer the lack of pipelines, but the electricity from renewable sources such as wind and solar will require transmission, and large transmission lines are just as subject to NIMBYism and protests – in some cases more so because they are so large and visible. They will be challenged too, with the unintended effect of significantly setting back renewable energy production.

No one wins if this happens.

–

What needs to be changed?

We have four main areas of concern, as follows:

The role of the Governor in Council (the federal Cabinet, or GIC)

Bill C-69 assigns new responsibilities to the Governor in Council (GIC – meaning the the federal Cabinet). In particular, the bill obliges the GIC to second-guess the regulator. This provision is new, and – however well- intended – undermines previous jurisprudence and will lead to new rounds of court challenges.

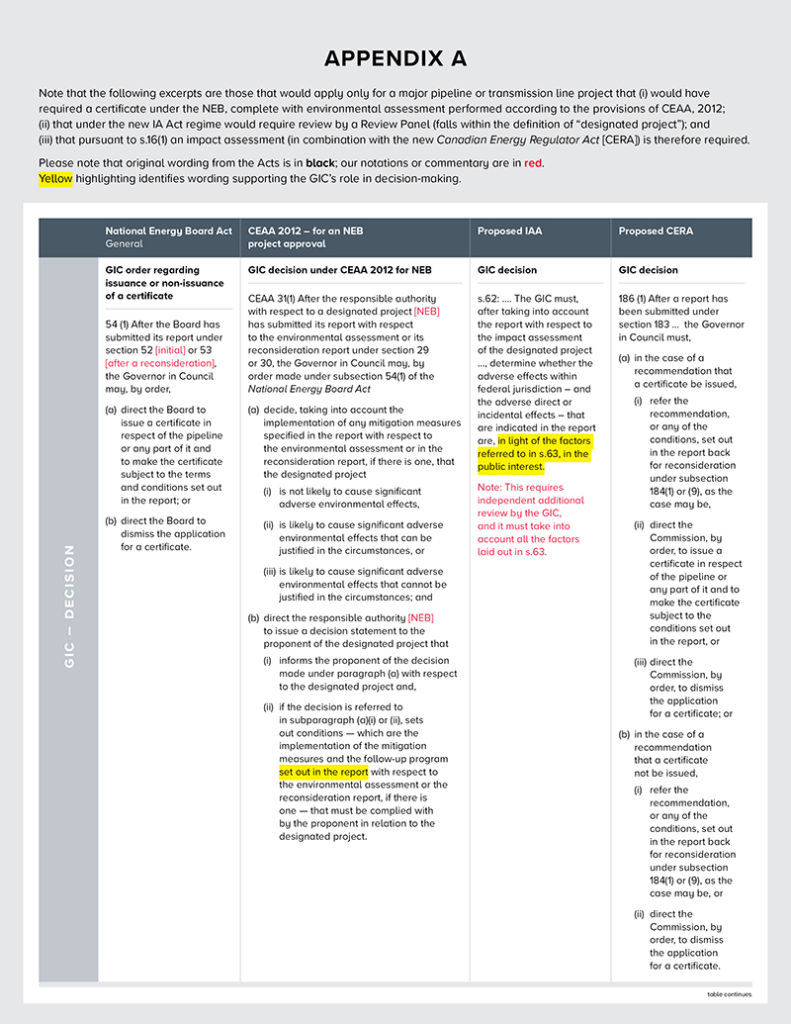

• Under the current legislation – the combination of the National Energy Board Act (NEB Act) and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act 2012 (CEAA 2012), the GIC must issue a decision statement to the project proponent to inform them about whether or not the project is approved. As set out in Sections 31(1) and 52(1) of CEAA 2012, that decision must be based on whether or not there are significant adverse effects; and if so, whether those effects are justified.

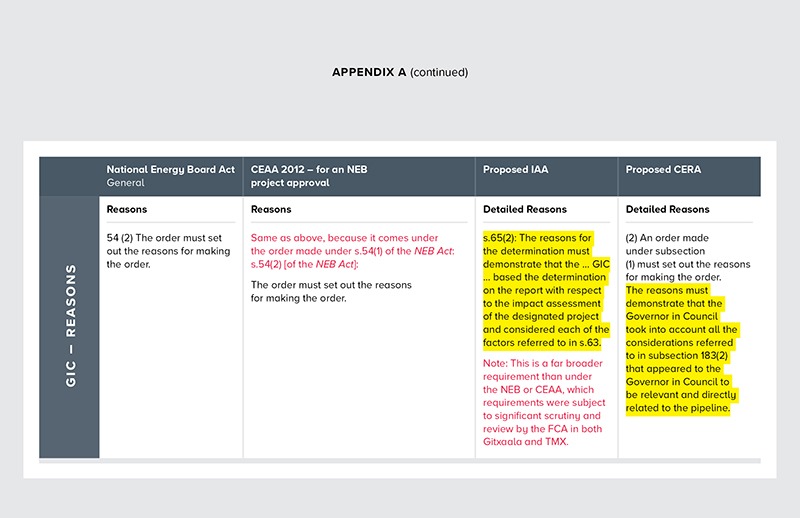

• The Federal Court of Appeal, particularly in Gitxaala and TMX, exhaustively reviewed the role of the GIC and based on the existing legislative scheme – the combination of the NEB Act and CEAA 2012 – confirmed that the decision-maker was the GIC; that it was not up to the court to question how or what that decision was based on; that the test was, under the legislative regime, one of reasonableness; that the only way to challenge a GIC decision was to question whether the Board’s report was really a “report,” i.e., was not deficient; and that, with an acceptable report, the GIC was not obliged to investigate further and that its decision could not then be challenged.

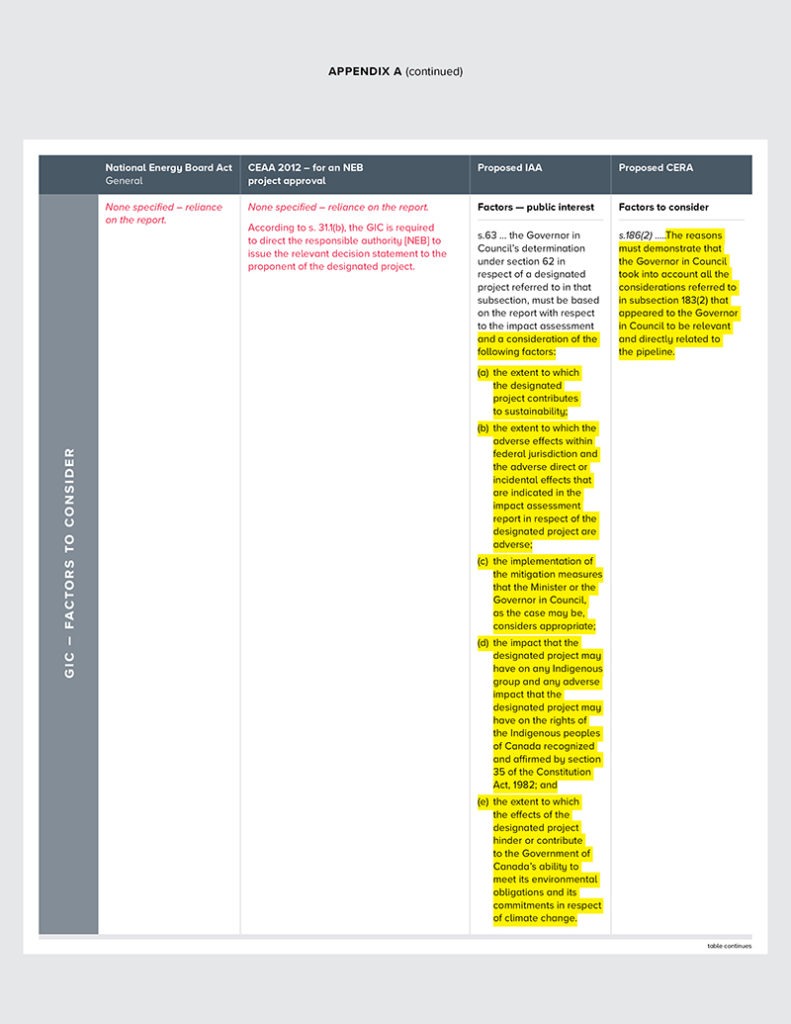

• Section 65(2) of the IA Act, however, significantly adds to the factors that the GIC must consider, even after the process has been completed and a report provided. The new language would put a significantly greater onus on the GIC to review any report or report recommendations – in effect, obliging the GIC to second-guess the regulator. Not only is it nonsensical to ask politicians to second guess an extensive, detailed process by experts, it will throw open the opportunity to challenge any GIC decision in court.

• The language set out for decision-making by the GIC in the IA Act should not be expanded this way, but revert back to what has been opined on and approved by the courts. See Appendix A for a comparison of the language of today (NEB Act and CEAA 2012) versus what is proposed in Section 65(2) of the IA Act for GIC decision-making.

The NEB

The NEB needs to be modernized and improved. But replacing the NEB’s entire project approval process – by moving it to a different agency that operates under a different set of procedures – means losing the years of court review, analysis and approval that we now finally have, associated with the existing NEB project review process.³

• First choice: Fix the NEB rather than replace it. After multiple challenges, the courts have upheld the NEB’s administrative and project approval processes, often specifically referring to – and allowing the process to rely on – the long-established expertise and experience of the NEB as the lifecycle regulator.? Replacing it and changing the project approval process will negate all of this prior jurisprudence, opening the system up to an entirely new round of court challenges. The NEB needs improvement, but the required improvements can be accomplished separately by removing Part II of Bill C-69, and amending the National Energy Board Act (the NEB Act) instead. Much of the language of Part II can in fact be repurposed to amend the NEB Act, in particular for the governance improvements that can be made.

• Second choice: The courts have ascribed major importance to the experience and expertise of the lifecycle regulator (including the ability of Cabinet to rely on recommendations). If the NEB must be replaced, it is critically important to keep the experience and expertise of the lifecycle regulator as a major part of the project approval process. To this end, a majority of people on a Review Panel, including the Chair, should be from the lifecycle regulator – not the opposite as is proposed in section 47 of the IA Act. In addition, any such Review Panel for major energy projects should be directed to use the rules of procedure set out currently in the National Energy Board Rules of Practice and Procedure.

Duty to Consult

The courts (again, Gitxaala and TMX being the most senior recent decisions) have now provided deep clarity on what is required for the Crown to fulfill its duty to consult with Indigenous communities pursuant to section 35 of the Constitution. The inclusion of the reference to UNDRIP, even in the preamble, particularly in the absence of any other judicial interpretation of what it might mean in Canadian law, will throw out the certainty that we have finally achieved in this regard. This is not a comment on UNDRIP itself. Our concern is that it should be interpreted in terms of Canadian law separately. It should not be the responsibility of a regulator to do so in any case – and if it does, any interpretation it applies will be challenged by project opponents.

New, broadly described factors

There are various new factors and requirements that would have to be considered at various stages of the review process. Some are so new and so broad that any decisions as to how they are interpreted or applied will open up court challenges. Lack of definition will leave major holes for the courts to fill. These new, undefined requirements (such as “meaningful public participation” and “sustainability”) must be more precisely defined. It is not the job of the regulator to determine policy.

It is hoped that if adequate definitions are not included in the bill itself that this clarity be provided by way of regulations.

–

Conclusion

If we do not address these concerns about Bill C-69, the country will go back to square one – the existing jurisprudence will no longer apply, because a number of aspects of the bill would create new, expanded and untested processes.

We urge both the Senate and the federal government to look at these issues very carefully, as they are critical to ensuring that once any project is indeed approved, it will not then be subject to years of unnecessary court challenges and delays.

¹ And various cases referred to therein.

² In TMX, with respect to the entire NEB process only a very specific, and fixable aspect in terms of scope – not process – was found wanting. The rest of the process was accepted.

³ Please note that we have not addressed similar concerns with respect to nuclear or offshore projects – not because there aren’t similar concerns about removing the project approval function from the lifecycle regulator, but because of our own limited time and resources.

? See the portions of the decision excerpts in Appendix A highlighted in yellow.

Appendix A

Note that the following excerpts are those that would apply only for a major pipeline or transmission line project that (i) would have required a certificate under the NEB, complete with environmental assessment performed according to the provisions of CEAA, 2012; (ii) that under the new IA Act regime would require review by a Review Panel (falls within the definition of “designated project”); and (iii) that pursuant to s.16(1) an impact assessment (in combination with the new Canadian Energy Regulator Act [CERA]) is therefore required.

Please note that original wording from the Acts is in black; our notations or commentary are in red. Yellow highlighting identifies wording supporting the GIC’s role in decision-making.