As the fifth round of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) renegotiations kick off this week in Mexico, uncertainty over the future of the pact lingers.

The demands by the U.S. such as scrapping the agreement’s dispute settlement mechanism and stricter rules of origin for auto manufacturing are among a growing list of “take it or leave it” demands by the Americans that Canada and Mexico will find hard, likely impossible, to agree to. If these are serious demands and not merely negotiating ploys, the future of the pact is in grave doubt.

Last month, we took a look at different scenarios that could unfold if the U.S. leaves NAFTA, and the tariff-related impact each would have on the top 10 exports to the U.S. from each of the four western provinces. Another aspect to consider is how jobs in western Canada could be affected by a U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA. (Note: jobs related to exports to Mexico are not included because if the U.S. withdraws from NAFTA, the Mexican and Canadian governments have stated that the agreement will remain in place between Canada and Mexico. Also, Statistics Canada does not track jobs related to exports to Mexico.)

A significant number of western Canadian jobs are linked to exports to the U.S.

In 2013, 13 per cent of all jobs in Alberta were tied to U.S. exports. In Saskatchewan and Manitoba, 10 per cent of total employment was linked to exports to the U.S. while nine per cent of B.C.’s total jobs were supported by U.S.-bound exports.

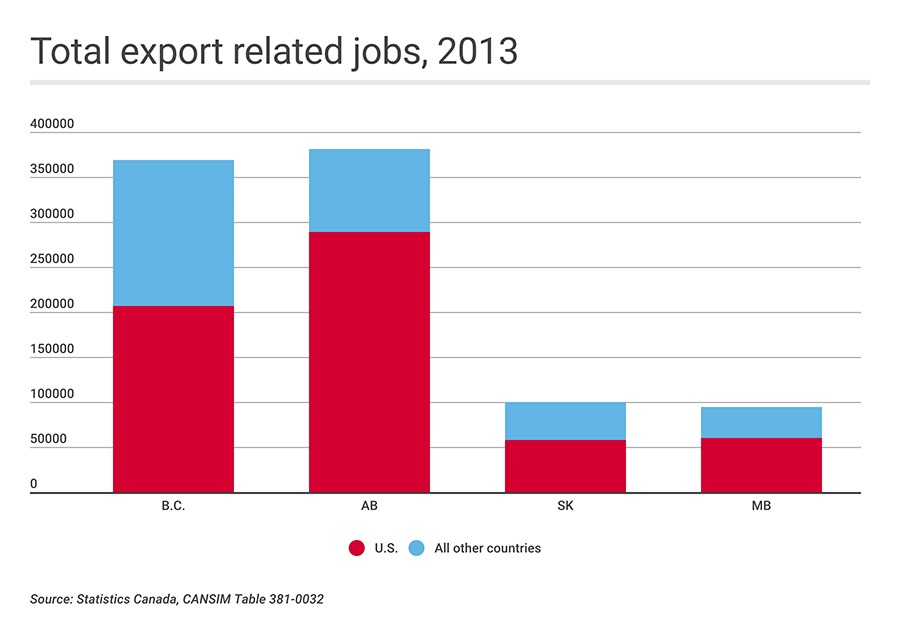

As shown in the figure below, in each western province, more export-related jobs are tied to exports to the U.S. than exports to all other countries combined. This is because about 70 per cent of the value of all exports shipped out of western Canada are destined for the U.S. market.

*Note: 2013 is the most recent year data is available for on jobs related to exports. Although it is several years old, it still provides an idea of the amount of jobs reliant on exports to the U.S.

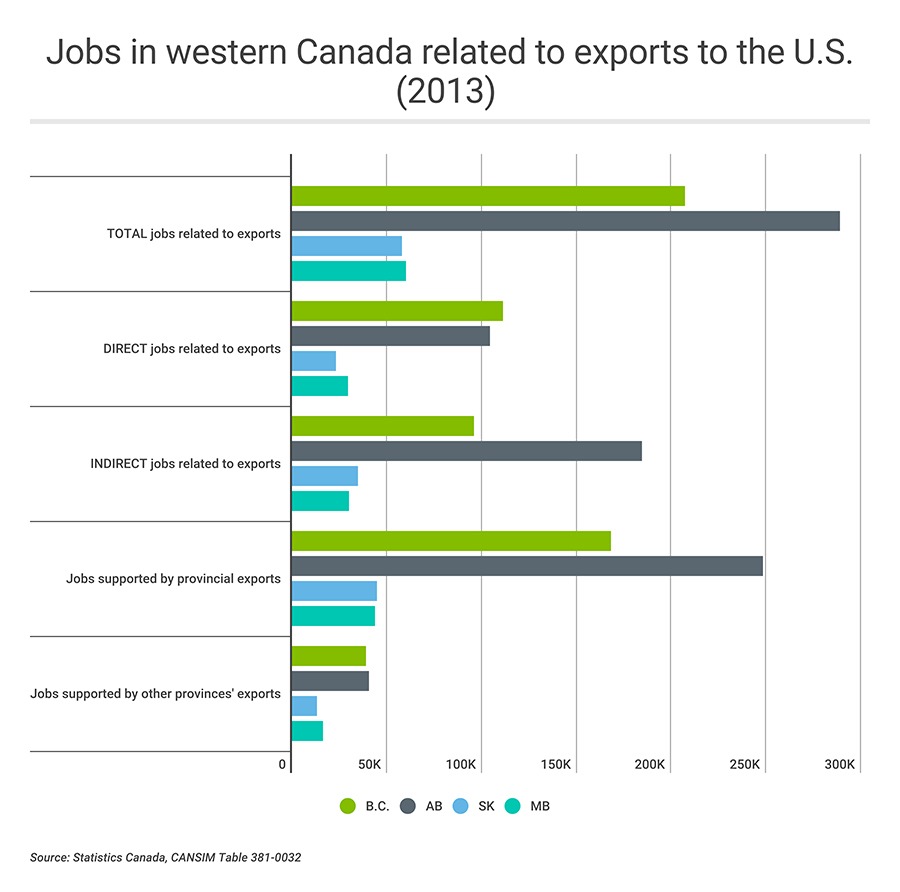

The next figure shows the number of jobs supported by goods exports to the U.S. for each western province. Since there is no provincial-level data on service exports, these jobs figures almost certainly understate the case.

The next figure shows the number of jobs supported by goods exports to the U.S. for each western province. Since there is no provincial-level data on service exports, these jobs figures almost certainly understate the case.

Of the western provinces, Alberta has the largest number of jobs tied to U.S.-bound exports. This is because about 85 per cent of the value of Alberta’s total exports go to the U.S., compared to 48 per cent for Saskatchewan, 53 per cent for B.C. and 67 per cent for Manitoba. The value of oil impacts the picture in Alberta; last year 63 per cent of the value of total provincial exports to the U.S. was from crude oil exports.

Of the western provinces, Alberta has the largest number of jobs tied to U.S.-bound exports. This is because about 85 per cent of the value of Alberta’s total exports go to the U.S., compared to 48 per cent for Saskatchewan, 53 per cent for B.C. and 67 per cent for Manitoba. The value of oil impacts the picture in Alberta; last year 63 per cent of the value of total provincial exports to the U.S. was from crude oil exports.

In the Prairie provinces, there are more indirect than direct jobs tied to exports to the U.S. For example, indirect jobs include employment in all the service and equipment companies supplying oil and gas extraction companies in Alberta and Saskatchewan, and the majority of these products are sold to the U.S. B.C. has a slightly higher number of direct jobs than indirect jobs tied to its U.S. exports.

Most export-related jobs are due to exports originating from the western provinces themselves, but a portion are tied exports from other provinces. This makes sense, considering 76 per cent of all Canadian goods exports and more than half of service exports are sent to the U.S.

What if the U.S. leaves NAFTA?

If the U.S. withdraws from NAFTA, our trade with the U.S. is not going to stop. It will, however, get more expensive. NAFTA, and its predecessor the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA), eliminated tariffs on most products traded between Canada and the U.S., with a few exceptions. Scrapping these deals will bring back higher, World Trade Organization (WTO), tariff schedules. It the short term, it could also give President Trump a tariff stick to inflict damage in certain sectors. We need look no further than the ongoing Canada-U.S. softwood lumber dispute to see how this can happen. Softwood lumber is excluded from NAFTA, and the U.S. Commerce Department recently imposed anti-dumping and countervailing duties – averaging 21 per cent combined – on all softwood lumber imported from Canada. Canada is now appealing the decision, and as in the past, will likely win the appeal. But the process takes a couple years, and in the meantime, U.S. softwood lumber producers earn higher profits and hope the duties will force Canada to make concessions in the continuing softwood lumber agreement negotiations.

The more barriers to trade, the more difficult it can be for exporters. If the U.S. leaves NAFTA, there would likely be some jobs losses but it is hard to predict how extensive these would be. After more than 20 years of NAFTA, our economies are integrated and we rely on trade with each other in the sophisticated supply chains that have been developed. Any increase in tariffs faced by Canadian exporters would likely be passed on to the end (American) consumer.

Western Canada’s trade transportation infrastructure and west coast ports also gives us an advantage over other regions in Canada – access to the growing markets in the Asia-Pacific. Already, this makes the West less reliant on the U.S. than central Canada; 45 per cent of all jobs in Canada related to exports to the U.S. are based in Ontario, compared to 30 per cent being based in the western provinces. (Quebec benefits from almost 21 per cent of total Canadian jobs related to exports to the U.S., while the remaining 4.5 per cent of jobs are distributed throughout the rest of Canada.)

If the next few days of negotiations deteriorate in Mexico and the U.S. decides to quit NAFTA, western Canada’s best option to offset related job losses is to further diversify trade with countries across the Pacific. Westerners should push Ottawa to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership and conclude trade negotiations with the Pacific Alliance trade bloc without delay.

– Naomi Christensen is senior policy analyst at the Canada West Foundation